In the last few years, Western Australia has been exporting a curious little coral whose true identity has been something of a mystery. In outward appearance, its overall shape is nearly identical to the true “scoly” (Homophyllia australis), with both typically having just a single large and colorful polyp. But subtle differences in their relative size and coloration have hinted that these two are not the same. Now, thanks to a recently published taxonomic revision for this group of lobophyllids, we finally have an answer to this question with the description of a new species, Micromussa pacifica.

While it might look a lot like a scoly, the genetics and skeletal morphology of M. pacifica show it to be a very different type of coral. Both belong to the recently recognized family Lobophylliidae, which includes a mix of familiar aquarium groups (acans, lords, most chalices and open brains). These corals all share some similarities regarding the shape of their septal spines, these being quite large and somewhat tooth-shaped. Aquarists have long been aware of this fact, as these are the corals most likely to have their tissue damaged during shipping or to pierce through a plastic bag.

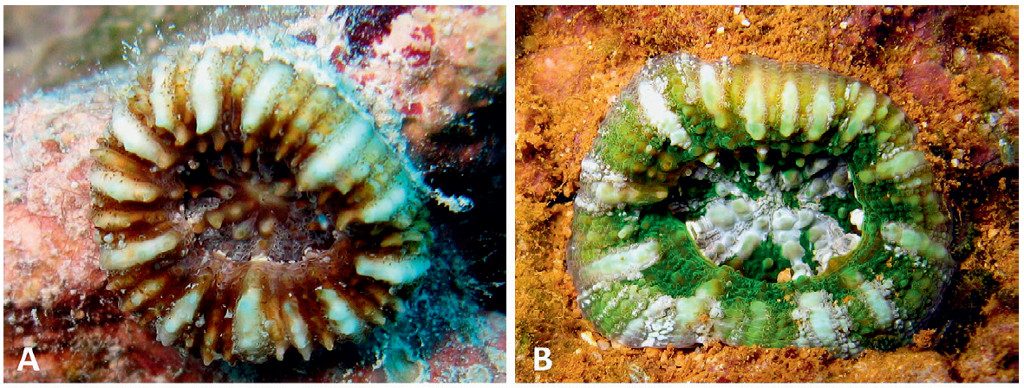

To understand why the Homophyllia corals are distinct from the Micromussa corals, we have to look at a few traits which can be challenging to observe without the aid of some magnification. One of the more easily spotted differences relates to the thickness of the septa. In Homophyllia, these vary in width, alternating between thicker and thinner septa as one circles around the polyp. Compare this to Micromussa, where the septa are more or less all of the same thickness, and it becomes fairly simple to recognize one from the other. This trait can be seen to some extent in living specimens of M. pacifica, especially when the tissue overlaying the septa is of a contrasting color, highlighting how even and repetitious these are.

Micromussa pacifica (left) & Homophyllia australis (right). Note the differences in septal evenness and where, in relation to the center of the corallite, the tallest septal spines occur. Modified from Arrigoni et al 2016

At a finer scale, the surface texture of the septa and the spacing of the spines is also quite informative. As the authors put it, “Micromussa is characterized by medium tooth spacing (0.3 – 1.0 mm) and by strong, pointed and scattered septal side granulation, whereas Homophyllia shows wide tooth spacing (> 1.0 mm) and weak, rounded, and uniformly distributed septal side granulation.” These are fairly subtle distinctions which most aquarists will be hard-pressed to discern, but a somewhat more visible difference to look for is how the height of the septal spines change within a polyp. For the true scoly, the spines are taller towards the center of the polyp, whereas these increase in height towards the outer wall in species of Micromussa.

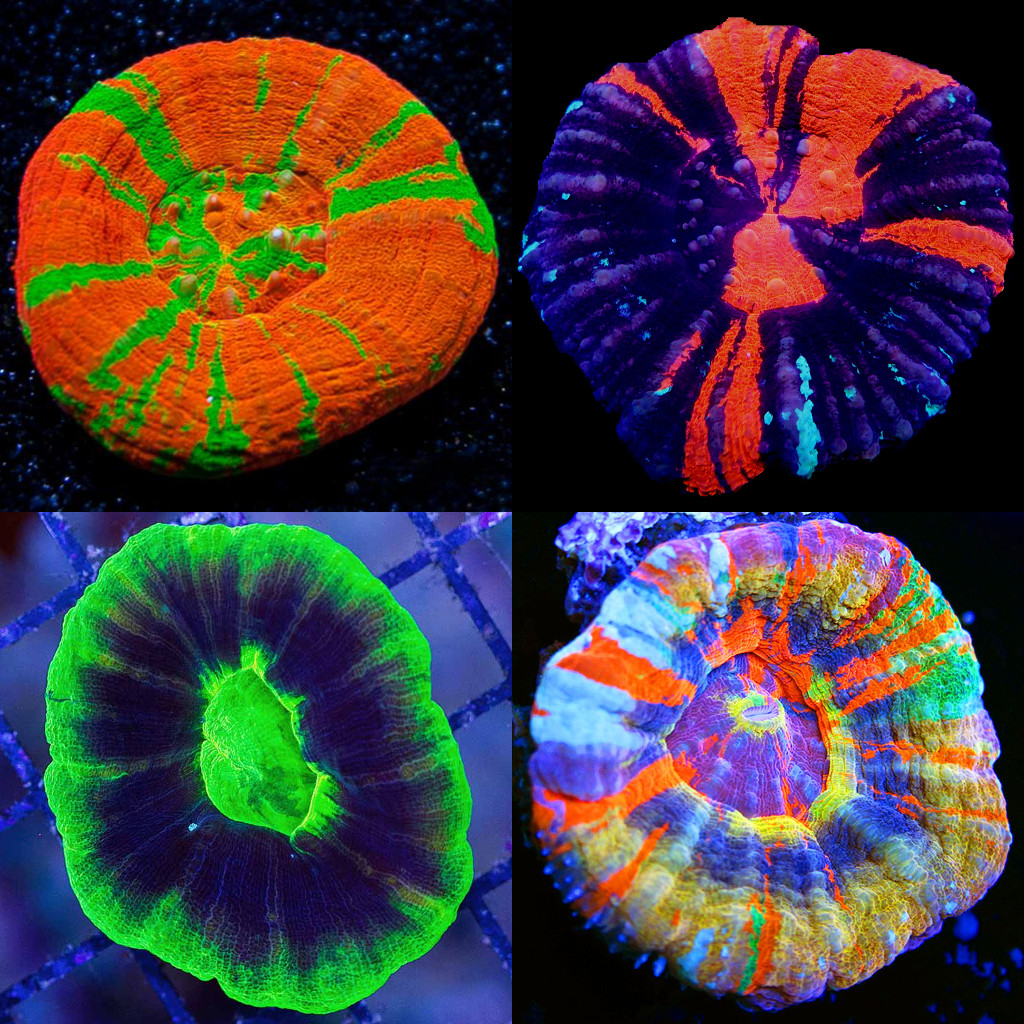

Popular color morphs of Homophyllia australis, clockwise from top left: Bleeding Apple, Warpaint, Master, UFO. Credit: Unique Corals, unknown, Sexy Corals, Aqua SD

Of course, size is one of the easier tells—they call them Mini Scolys for a reason. The largest specimens of M. pacifica are reported to reach just 25mm in diameter, compared to the considerably larger H. australis, which can easily grow to twice this size. There’s also a greater tendency for M. pacifica to form multi-polyp colonies. Color is also a useful clue, as the Mini Scoly frequently has a symmetry to its radial patterning that is often lacking in H. australis. Familiar color morphs, like the “Bleeding Apple”, “Warpaint” and “Master”, are unique to the bigger scoly, and, while M. pacifica can often come in attractive shades of green, blue, red and orange, it usually tends toward the drabber side of the spectrum.

This polystomatous colony from Bali shows one of the nicer looking variations seen in Micromussa pacifica. It had been misidentified as Acanthastrea maxima. Credit: Eddie Hanson

In the wild, M. pacifica is known mostly from subtropical reefs in the South Pacific, with the type locality being at the Gambier Islands of French Polynesia and occurring west into New Caledonia, and Lord Howe Island. The population being collected for the aquarium trade in Western Australia is not mentioned by these authors, though it is presumably of this same species. There have also been similar corals exported from Bali, often misidentified as the Red Sea endemic Sclerophyllia (=Acanthastrea) maxima, which are said to come from areas experiencing cooler upwellings.

The Scoly and the Mini Scoly seen side by side. Can you tell which is which? Credit: Arrigoni et al 2016

The Mini Scoly grows on hard substrates and is found in protected habitats experiencing heavy sedimentation at moderate depths (10-40 meters), though it is also reported from outer reef slopes. It occurs alongside H. australis, with both showing similar distributions and ecological preferences; however, the true geographical extent of these species in the Pacific remains somewhat unclear, with unconfirmed reports from the Marshall Islands suggesting that at least one of these species is quite widespread. For aquarists, it’s important to recognize that these are corals which prefer lower-light, lower-flow and cooler conditions, and that the difficulty many have with these species long-term likely stems from failing to recreate these conditions in captivity.

Arrigoni, R., Benzoni, F., Huang, D., Fukami, H., Chen, C.A., Berumen, M.L., Hoogenboom, M., Thomson, D.P., Hoeksema, B.W., Budd, A.F. and Zayasu, Y., 2016. When forms meet genes: revision of the scleractinian genera Micromussa and Homophyllia (Lobophylliidae) with a description of two new species and one new genus. Contributions to Zoology, 85(4).

0 Comments