Pair of Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp (Periclimenes colemani) on Asthenosoma sp. urchin.

Photo by Randi Ang

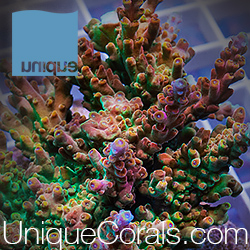

In today’s edition of “Inverts We Wish We Could Have” we find ourselves craving the Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp, Periclimenes colemani. The Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp is a supremely striking little shrimp found in the Indo-Pacific region around the Philippines and south towards Indonesia and Australia, at around 1-12 meters deep. They have bright white bodies covered in deep red spots and stripes, and have long, thin arms with small pointed claws. Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp are obligate symbionts, typically found in pairs, only living on certain species of sea urchins such as Asthenosoma intermedium and Asthenosoma varium. They are very tiny shrimp, typically measuring about 20 millimeters long with females being larger than males and having a much more round and stout abdomen.

A male Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp (Periclimenes colemani) on Asthenosoma sp. urchin.

Photo by Rickard Zerpe

Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp have evolved to have coloration and patterning that matches their normal host urchins. This is important for allowing them to blend in, helping them avoid visual detection by predators. However, if they are found by a predator, their second line of defense is the venomous spines of the host urchin which can inflict a nasty sting to would-be attackers. The shrimp reside on an area of the urchin’s test (shell) which is cleared of spines, presumably by the shrimp themselves – it is theorized that the shrimp clear an area of the host urchin’s spines, but the behavior of clearing the spines has not been observed. Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp have been found to remain on the same area, devoid of spines, for long periods of time without moving from their chosen position. They have not been found to harm or help the host in any way, indicating that their relationship is an example of commensalism. The shrimp likely feed on any foods that happen to pass them by, potentially feeding on some of the host urchin’s scraps.

Close-up view of a female Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp (Periclimenes colemani)

Photo by Randi Ang

Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp are another invert that we will just have to dream about because they are not collected for the aquarium trade and are not suitable for aquarium life. They are extremely tiny and would only be able to survive if provided with the proper species of venomous sea urchin. There is also a concern that in the process of being shipped and introduced to an aquarium, the shrimp could become stressed and leave the safety of their host leading to predation. It is not currently known exactly what Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp eat and aquarists may be unable to provide them with proper nutrients. As with many symbiotic marine species, Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp are highly sought-after subjects for underwater photographers and recreational divers and it is through those avenues that we may continue to enjoy this species in its natural habitat.

Pair of Coleman’s Urchin Shrimp (Periclimenes colemani) on Asthenosoma sp. urchin.

Photo by Randi Ang

References:

Bruce, A. J. 1975. Periclimener colemani sp. nov., a New Shrimp Associate of a Rare Sea Urchin From Heron Island, Queensland (Decapoda Natantia, Pontoniinae). Records of the Australian Museum, 29, no. 18: 485-502

Chace, Fenner A., Jr., and A. J. Bruce. 1993. The Caridean Shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) of the Albatross Philippine Expedition 1907-1910, pt. 6: Superfamily Palaemonoidea. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, no. 543

0 Comments