By Christine Williams

Inevitably as reefkeepers we do things that stress our fish and invertebrates: bringing new animals in, moving them from tank to tank, adding new inhabitants, or the like. Stress is the enemy of healthy fishes as it decreases immune function, allowing infections and parasites an easy ride. One substance used in food fisheries to help boost immunity is beta-glucan– a complex carbohydrate of natural origin. Long touted as an immunostimulant in animals from shrimps to humans, it is used for everything from wound treatment to cancer to diabetes care. Here we’ll dissect the myth from the science and show how beta-glucan can help you maintain a healthy reef aquarium.

What is Beta-glucan?

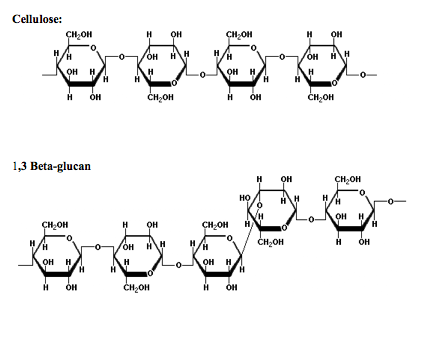

Beta-glucan is a carbohydrate molecule consisting of long chains of glucose molecules, much like cellulose. While cellulose forms long unbranched linear chains which can lie packed together (and which give wood its strength), the rings in beta-glucan form “kinks” which give the molecule a cylindrical shape. Neither cellulose nor beta-glucan is digestible, and so they either must diffuse through the skin or digestive system to be utilized by the body or are passed out as waste.

Cellulose, the major component of wood and vegetable fiber, is made of chains of glucose molecules connecting the #1 carbon of one glucose to the #4 carbon of the next. Beta-glucan uses the same linkage, but with an occasional 1-3 linkage thrown in, giving the molecule a twist.

Beta-glucan is found in many places, most notably in the bran of grasses such as barley, oats, and rye, and in the cell walls of mushrooms, algae, and yeast. A particularly good source of beta-glucan is in common Baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and this is the source of many of the over-the-counter beta-glucan supplements found in vitamin stores.

A Bit of History and Use

In the 1940’s, a crude yeast cell wall extract called Zymosan was first shown to stimulate the human immune system to fight bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic infections, as well as to help fight cancer. Sounds like a wonder drug, no? Unfortunately, Zymosan also caused undesirable side effects, and its use fell out of favor. Twenty years later, the active molecule in Zymosan was isolated and identified as beta-glucan, and research and use began in earnest and continues today.

The benefits of beta-glucan in human health are widely known and scientifically accepted, yet beta-glucan still sits at the border between accepted medical treatment and “nutraceutical”. It has been shown effective at reducing cholesterol: in order for your morning cereal box to have the label “Heart Healthy”, it must contain at least 750 milligrams of beta-glucan per serving. It has been used in diabetic patients to help regulate blood glucose, in burn patients to speed wound healing, and in cancer patients to stimulate the immune system to destroy cancer cells. In fisheries and aquaculture facilities, it has long been used in combination with vaccines to boost the effectiveness of the vaccine, and has been used anecdotally in ornamental aquaria, especially by seahorse keepers, for many years. Perhaps its greatest claim in both humans and animals is its effect as a nonspecific immune stimulator. To find out exactly what this means, let’s take a brief look at the vertebrate immune system.

Role in the Immune System

A convenient way to look at the immune system of vertebrates is to divide it into two arms: innate immunity and acquired immunity. Innate immunity encompasses all the ways a body is able to defend itself at birth: we have skin to prevent pathogens from entering our bodies, stomach acids to destroy the bacteria and fungi we inevitably ingest, and many chemical compounds which circulate in our blood and fight off invaders. Acquired immunity is that which your body produces in response to specific stimuli from the environment: antibodies. So how does beta-glucan fit into this system? No single activity explains all the things it is reported to do, but one is well known and characterized: the activation of macrophages. Macrophages (from the Greek, meaning “big eater”) are cells which reside in our tissues and act as phagocytes, or “eating cells”. Essentially they function as the body’s cleanup crew, engulfing foreign material and old dead cells and either digesting it or sequestering it away from the rest of the body. Even invertebrates are well equipped with macrophage-like cells that nonspecifically dispose anything they recognize as non-self.

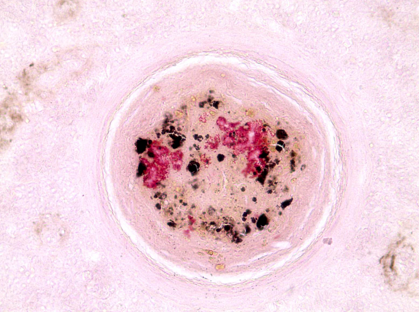

Macrophages surround dead and infective tissue forming a granuloma in a fish with mycobacteria. (courtesy M. Fast)

In order to begin its work, though, a macrophage needs to be activated. On its surface, the cell contains receptor molecules which serve as docking stations for foreign materials. When a pathogen such as a bacterium encounters a macrophage, it binds to the specific receptor putting the macrophage on alert. This macrophage can then engulf that bacteria, and importantly, it will secrete compounds which alert other immune system cells that an intruder is on the loose. Soon after, many parts of the immune system have received the alert, and are at the ready to fight.

Beta-glucan is able to activate macrophages so effectively because there is a receptor on macrophages (and on phagocytes in invertebrates) that fits beta-glucan like a lock and key. As soon as a macrophage “sees” beta-glucan (the beta-glucan molecule binds the receptor on the cell surface) it acts as though there is an infection, and activates itself and the immune cascade. Why is there a receptor for an oat polypeptide on an immune cell? Remember, beta-glucan is found in many other places as well, including the surfaces of fungi, so when the macrophage encounters beta-glucan, it acts as if it is encountering a fungal pathogen, and becomes activated. Interestingly, it has been found that beta-glucan mimics a compound produced by Vibrio species, a common marine bacteria, so this may explain why beta-glucan is useful in heading off bacterial infections. This receptor for beta-glucan is well conserved: it has been found on phagocytic cells in shrimp and prawns, crabs, fish, and mammals.

Use in Marine Animals

Even before this mode of action was determined though, food fisheries and aquaculturists had used beta-glucan to stimulate immune function, and in the past three years many studies have been done which prove beta-glucan’s effectiveness in shrimp, juvenile fish, and adult fish. The more money there is to make (and lose), the more people are willing to invest in research for animal health, and so the food fisheries are way ahead of the ornamental trade in using beta-glucan. So how, and more importantly, when should we use beta-glucan in marine aquaria? Typically it is available from vitamin and health food stores in tablet or powder form. A word of caution: read your labels! Nutritional supplements are not well regulated, and often a product claiming “500g Beta-glucan!” has some 1,3 beta-glucan, but the bulk is other forms which may or may not have the same activity. If you buy tablets, you can simply crush them, taking care to remove any coating the tablet may have (it likely won’t hurt anything, but it may affect solubility).

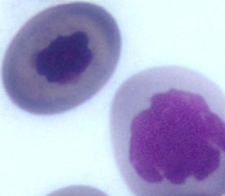

Angelfish infected with lymphocystis. Beta-glucan has been shown to increase fish’s immunity to lymphocystis.

Beta-glucan can be administered any time an animal is ill, is stressed, or will be stressed soon (for example, ahead of a tank move or transfer). In cases of infection, it can be added to the antibiotic regimen. The antibiotic will kill off the pathogen, and the beta-glucan helps by activating the macrophages to mop up the dead cells. Beta-glucan can be administered by immersion, by injection, or byfeeding. For immersion, it can be added directly to the aquarium after mixing it with tank water at 0.5 ppt (0.5 grams/liter or roughly 1.9 grams/gallon). This can be performed in a display tank or a quarantine tank. Most successful studies have administered the compound directly in feed. If you make your own frozen fish food, you can add 0.1% beta-glucan to the mix before you freeze it, and then feed as usual. It can be added to frozen packaged food as well by thawing the food , sprinkling the powder into the food, and feeding as usual. Alternatively, you can gut-load live Artemia (brine shrimp): mix beta-glucan into your Artemia culture the day before feeding them to your fish. This is a particularly convenient way to get beta-glucan into recently wild caught fishes: many do not yet take prepared or frozen foods, so while you are using brine shrimp to wean them to frozen or dry food, you can also be helping their immune systems.

While it is unlikely you can overdose beta-glucan, you certainly can overuse it. An animal has a finite amount of energy it can expend on metabolic and other functions at any given time. If its immune system is in overdrive, it will be at the expense of growth or reproductive capability. Also, it is uncertain yet whether the body becomes “tolerant” of beta-glucan; it may be that after prolonged exposure, the immune system does not respond as robustly as it did on first encounter. Some studies done in shellfish show a detrimental effect with continuous usage. Other studies advocate a 6 week on, 2 week off dosing schedule, but these were done in food fisheries where animals are arguably under constant stress. For now, the effects are unknown, so to be cautious, it is best to administer beta-glucan only when it is needed: during illness or stress, or prior to stress. I would not advocate using fish foods with beta-glucan in them as your normal feed (again, read your labels!). Save them for quarantined or hospitalized animals.

The use of beta-glucan in marine aquaria is not new, but has unfortunately largely been though of as anecdotal, unproven, and with an unknown mechanism of action. In fact, we do know at least one way that beta-glucan works in fish and invertebrates, and it may have other modes of action as it does in humans. By looking to our counterparts in aquaculture and food fisheries we can find many well established, well researched ways to improve the health of our animals, including further research on the use of beta-glucan.

0 Comments