By Richard Ross

Ethical discussion about almost every area of reefkeeping has been a part of the hobby for as long as the hobby has existed – What size tank do I need to meet my animals’ needs? Are some animals better left in the ocean? Do I really need a separate tank to treat a sick fish? Can we justify the resources we use for our aquariums?

The discussion of ethics in our hobby is both comprehensive and esoteric, having the potential to evoke extreme emotion as people argue for what they feel is some sort of moral high ground. Lately, some parts of the ethical discussion have heated up due to anti-aquarium groups working to curtail or even shut down wild collection for the hobby. As always, some of the anti-hobby positions are valid, and should make us examine and change our husbandry practices, while others are based on emotional, poorly constructed arguments. But, ethics are not as simple as people who want you to support their position often make them out to be. We need to be prepared to counter such ethical misstatements, both in others and ourselves. This starts with understanding and refining our own ethical stances s, since the better we will be able to understand and communicate our positions to others, the better the hobby can move forward.

There is lots and lots of life on wild reefs. Is it ethical to collect it and ship it halfway around the world to put in peoples living rooms? Perhaps the answer depends on how much suffering is caused to the creature’s in the process. (Photo by Richard Ross.)

A brief reminder to set the scene

Skepticism is a method, not a position. Officially, it can be defined as a method of intellectual caution and suspended judgment. As a Skeptical Reefkeeper, you decide what is best for you, your animals, and your wallet based upon critical thinking: not just because you heard someone else say it. The goal of this series of articles is not to provide you with reef recipes or to tell you which ideas are flat out wrong or which products really do what they say they do or which claims or which expert to believe – the goal is to help you make those kinds of determinations for yourself while developing your saltwater thumb in the face of sometimes overwhelming conflicting advice.

A certain point of view

A long, long time ago in a galaxy far far away, Ben Kenobi said ‘you’re going to find that many of the truths we cling to… depend greatly on our own point of view.’ Different points of view are critical to a healthy understanding of the ethical positions of others, and to avoid oversimplification and inconsistency in your own positions. (For instance, even the societally supported, seemingly obvious and simple ethical position ‘Thou shalt not kill’ is easily, and commonly abandoned in reality during times of war, or in the course of law enforcement.). My hope is that after thinking about ethics that reefkeepers might become less likely to dismiss different ethical stances outright, as well as the people that hold those stances. If we make a real effort to understand and respect others’ positions, we can use information that comes from those discussions to further refine our own positions.

Is it ethical to bullseye Womp Rats in your T-16? It depends on a certain point of view. (Image from Google Images/Doug Savage.)

In every reefkeeping ethical discussion I have been involved in, everyone, no matter how different their ethical points of view might be, has had the same goal; to do their best to help make animals lives better. So, if you find yourself arguing an ethical point remember that most probably, the person you are engaged with believes their position will make animals lives better as strongly as you believe your position will make animals lives better.

What are ethics anyway?

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, involves exploring concepts of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ conduct, but ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ mean different things to different people. Some people feel that there are absolute ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ that are unchangeable and apply equally to everyone independent of what an individual might think, while others feel that there are ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ that are not absolute and can change over time or when new information becomes available. Sam Harris moves at a different angle describing a ‘moral landscape’ that may have many peaks corresponding to different ‘rights’ and many valleys corresponding to different ‘wrongs’ with none of the ‘rights’ or ‘wrongs’ being necessarily better or more absolute than the others, just different. Philosophers have talked and debated for thousands of years and written millions of words about this kind of stuff, so, for the purposes of this article, lets consider a more practical approach and build on the idea that ethics is, in general, concerned with how creatures should be treated in regards to minimizing their suffering and maximizing their well being. An action that increases well being of a creature can be thought of as ‘right’, while an action that increases the suffering of a creature can be thought of as ‘wrong’. This kind of generalization really seems to get at the focus of what we as reefkeepers are after as it seems we are looking to maximize the well being, and minimize the suffering, of the creatures in our care.

Worth, value and suffering

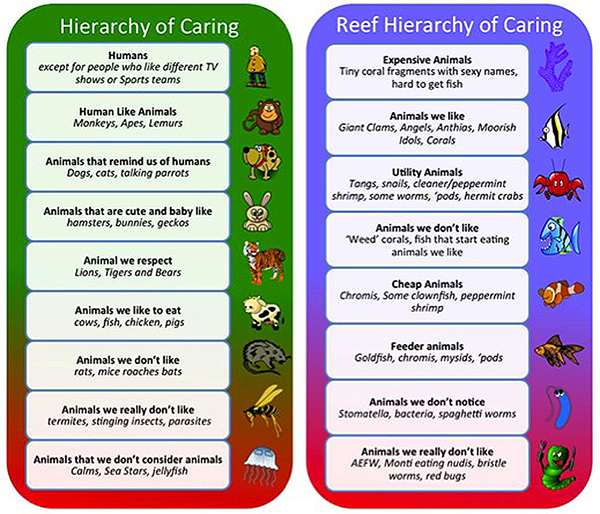

We tend to care more about the well being of animals depending on our emotional attachments to them, as well as their perceived(*1)usefulness or danger to us. Placements on the hierarchy will change over time, and everyone does not have the same hierarchy. The above hierarchies are meant to illustrate some of the often unconscious reasoning that determines a creatures place on the hierarchy.

No matter how magnanimous we want to think of ourselves, we still treat some living creatures differently from other living creatures. The reasons behind this are usually a combination of monetary worth (the more expensive the creature is the better we take care of it, the less expensive it is the more disposable it is), perceived emotional/practical value (do we like to cuddle with the creature? Does it scare us? Does it taste good?), and perceived ability to suffer (That dolphin sure made a ruckus for a long time when those Cove guys went after it, but that lobster stopped moving right after it hit the boiling water). We are generally going to spend more of our limited time, resources and money taking care of a sick child than a sick gorilla, a sick dog, a sick rat, a sick fish, or on a sick snail. In reefkeeping we generally seem to spend more of our limited time, resources and money taking care of an ailing system, rather than a sick fish, sick coral, sick snail, or a sick amphipod. In the practical world, our limited resources seem to make such an ‘ethical hierarchy’ necessary to make reasonable decisions about animal care – just how much time and resources should we expect a home reefkeeper to spend on a sick fish? The answer ‘whatever it takes’ is a nice feel good position, but doesn’t seem to stand up to the test of reality and practicality in both reefkeeping and in the wider ethical world.

It seems difficult to ask society to worry about a single sick fish in a home tank, when wild fish are so often treated as trophies. (Photo from Google Images.)

Owning a pet of any kind seems to incur an ethical responsibility because that animal is completely dependent on its owner for everything it needs. The pet owner has chosen to take on this responsibility and therefore should ‘do right’ by the animal. However, that ethical responsibility is often tossed away due to practical considerations. For instance, it is sadly not uncommon for a dog owner to euthanize (have killed(*2))a sick or injured dog because they don’t have the funds to pay for the animal’s convalescence. It is a tragic situation, but given the choice between spending thousands of dollars for dog knee surgery, along with 6-8 weeks of follow up care and time off work, or feeding human children, feeding human children comes first. Most people feel compassion and understanding for those that are in such a horrible situation. We see the same sort of thing when a new reefkeeper, with their small, low cost aquarium, has a fish in their reef that infected with the parasite Cryptocaryon irritans (Marine Ich) and discovers that to treat the fish some sort of extra ‘hospital’ tank is required because treatments for the parasite will kill corals or compromise the bacteria that are responsible for biological filtration of the aquarium killing all the animals in the aquarium(*3). Can we reasonably expect such a person to spend even more money and resources on a hospital tank, and more importantly, can we reasonably expect them to properly carry out an effective and safe treatment regimen or will trying to save its life cause the animal to suffer more than humanely administered euthanasia?

About 400 tons of jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi) are caught by a Chilean purse seiner – are such practices ethical? Does the need to eat trump ethics? (Photo from Google Images.)

The answers to these questions are made even more difficult because of how, as a society, we treat fishes. We kill and eat fish. Lots of fish. So much so that some scientists predict that we will soon overfish the capacity of the oceans. When we catch fish to eat them, they often die a horrible death, being hooked onto the deck and hit with a stick until they die, or caught en mass in huge nets, crushed by the weight of their peers, then allowed to suffocate on the deck out of water or left to die slowly in a ‘live well’ with no circulation or aeration as ammonia and other toxins build up in the water. Given the sheer mass of fish that are killed every day for human consumption, with most people giving little thought to their well being, suffering, or impact on the planet as a whole it becomes difficult to feel ethical outrage when someone decides to not spend time and resources to save one small pet fish.

It seems like there is something important about intent in regards to our ethical intuitions in these situations. Someone who wants to keep a sick pet alive but simply can’t afford to, or their lifestyle has changed dramatically for any number of various reasons, generally is met with understanding. Someone who is bored, or just doesn’t want to exert the effort needed to keep a sick pet alive is generally met with vitriol. But, is the vitriol appropriate as long as the suffering of the animals in question is minimized or removed completely? Given the amount of fish killed every day for food, would it really be such a bad thing if people who needed to get out of the hobby for any reason, after making the attempt to give away the pet fish to a suitable home, decided to humanely euthanize the fish? It seems like euthanasia may be a much better solution over letting the fish slowly die from neglect based on social pressure due to distaste around euthanasia.

Coral eating hitchhikers like this 3 foot long Eunicid worm are a bane of reefkeepers, but they are amazing animals in their own rights. What are our ethical responsibilities regarding such pests? (Photo by Richard Ross.)

Surely we can feel we hold the moral high ground when someone wants to purchase an animal just to intentionally kill it, right? Not so much. In the pet world, there are tons of animals sold every day just to be killed – every day, guppies, goldfish, black worms, brine shrimp, mysids, daphnia, and crickets are sold for the express purpose of being killed to feed our pets. Even various wild caught damselfish or decorative shrimps and crabs are sometimes purchased as feeders for difficult-to-feed reef animals. As we discussed in the realm of human food, most people’s brains are able to do a ethical shift when it comes to the suffering of animals used for food because food is well, food. People and animals need to eat and eating live animals is part of nature. Most people even go so far as to say they want food animals to be treated as humanely as possible, but that ‘as possible’ is a slippery move because it generally refers to the expense of the animal as the less expensive the animal is, the less ‘possible’ it is to spend money to treat it humanely. To make it easier for people to deal with, the conditions that many of these food animals, both for human and animal consumption, are often relegated to hidden areas where the person buying the food animal won’t see potentially disturbing conditions.

Many species of reef fish commonly kept in reef aquariums laid out for sale and cooking in a Bornean street market. One person’s pet is another person’s meal. (Photo by Rich Ross.)

Perspective

Reefkeeping is a luxury hobby. You need to have free time, space and funds to keep a reef in your living room. And because the reefkeeping hobby is a luxury, ethical discussions can get a bit odd. Worrying about the ethical considerations of spending money on a pet fish in your living room quickly seems bizarre when one considers spending that same money on items that other humans need simply to survive.

Think of this from an equipment standpoint – the $1500 spent on a new protein skimmer to help keep exotic reef animals alive in your living room could have been used to supply fresh water to a village that has no fresh water, could inoculate children from debilitating disease, could feed a family of 4 for weeks. Thinking it through like this really puts the aquarium hobby in perspective – we use so much water, electricity, lumber, glass, plastic, packaging material, jet fuel and other resources for our hobby, how can we ethically justify such an endeavor? Tim Minchin ironically sums this up by considering the wine he loves to drink instead of aquarium animals:

“I just feel guilty ‘cause I know that that £7.50 odd that I spend most days on Cabernet Sauvignon could probably have been better spent buying some ****ing Somalian village a pump… But that’s why I savour it. Nothing taste as good as that sip of wine you know could’ve inoculated an infant against tuberculosis. THAT’S a ****ing guilty pleasure.”

For me, the takeaway isn’t to feel guilty about our choice to use money to put reef animals in our living rooms and it isn’t to stop keeping reef animals in our living rooms. Just about any hobby that anyone is involved in takes resources – skiing, four wheeling, eating salmon, recreational fishing, scuba diving, painting, sky diving, glass blowing, stamp collecting, etc. all have their impact on the world. For me, the takeaway is to appreciate the idea that I even have such a choice and to do the best I can with keeping the animals in my care alive, and to continue learning how to better keep them alive and thriving. Simply realizing that I am fortunate to be able to take part in reefkeeping has also spurred me to give more support to help humans that need it, as well as more support to the natural habitats that our reef animals come from.

The ‘Tang Police’ are concerned with making sure these fish are put in appropriate sized aquariums, but why the focus Tangs and not other fish? (Image by Reefbloke.)

Last thoughts

Ethical discussions can feel like an infinite regress – every time you feel like you have a handle on things, you realize that there is more that you don’t have a handle on. I hope that this article serves as food for thought and spurs more rational, open discussion of the idea of ethics in reefkeeping, and I encourage anyone with questions to post them in the comments section below.

Notes

*1 – I say perceived ability to suffer because scientifically quantifying suffering is difficult at this time, and I would like to avoid an emotional discussion that delves into the question of do fish feel pain when you hit them on the head on the fishing boat, or are they just flopping around, as Descartes maintained, like a broken machine. It does seem clear that animals with a brain and a nervous system react in ways that appear to be suffering when exposed to negative stimuli, and for our discussion, such reactions can be thought of as suffering.

*2 – I think it is interesting to explore the ethical implications of having someone do something for you that you aren’t willing to do yourself. For instance, would as many people euthanize their dogs if they had to do the killing themselves? Would Westerners eat as much meat as they do if they had to kill it themselves? If someone is unwilling to ‘put down’ a sick pet or kill an animal to eat it seems ethically dishonest to have someone else do it for them.

*3 – There are many in tank Marine Ich treatments sold commercially, but the efficacy of such products doesn’t stand on any firm ground. For more discussion of Marine Ich and Skeptical Reefkeeping please see Skeptical Reefkeeping part I, “Are you sure that that thing is true, or did someone just tell it to you?” available here:http://www.reefsmagazine.com/forum/r…hard-ross.html

Further Reading

Peter Singer – http://www.princeton.edu/~psinger/

Sam Harris – http://www.samharris.org/

Tim Minchin – http://www.timminchin.com/

0 Comments