By Rich Ross

In our hobby, there tends to be mostly a supermarket approach to purchasing animals – you go to a store and select the animal you want from an array of holding tanks containing animals waiting for a new home. While such a selection seems great, it also creates an environment that may engender impulse buys rather than considered choices, makes us feel that instant gratification is the norm, as well as making us feel that somehow, for various reasons, any animal is worth a try in any tank. As people who say we love the reefs, and the animals that live on them, perhaps we should spend more time considering, and getting others to consider, which animals are appropriate for which tanks and which reefers. In Skeptical Reefkeeping 7 we took a general look at ethics and how they relate to our hobby. In this installment, we’ll look at some of the “how”s and “why”s we choose animals for our tanks, why we might think all aquarists are on the same page, and some ideas about how we might make more informed choices regarding the creatures that we put in our glass boxes.

New fish are always exciting, but are more exciting when forethought is put into the fish before purchase. Photo of a recent shipment from Live Aquaria by Rich Ross.

A Brief Reminder to Set the Scene

Skepticism is a method, not a position. It can be defined as a method of intellectual caution and suspended judgment. As a Skeptical Reefkeeper, you decide what is best for you, your animals, and your wallet based upon critical thinking, not just because you heard someone else say it. The goal of this series of articles is not to provide you with reef recipes or to tell you which ideas are flat out wrong or which products really do what they say they do or which claims or which expert to believe. The goal is to help you make those kinds of determinations for yourself while developing your saltwater expertise in the face of sometimes overwhelming, conflicting advice.

Who Should Get What, When?

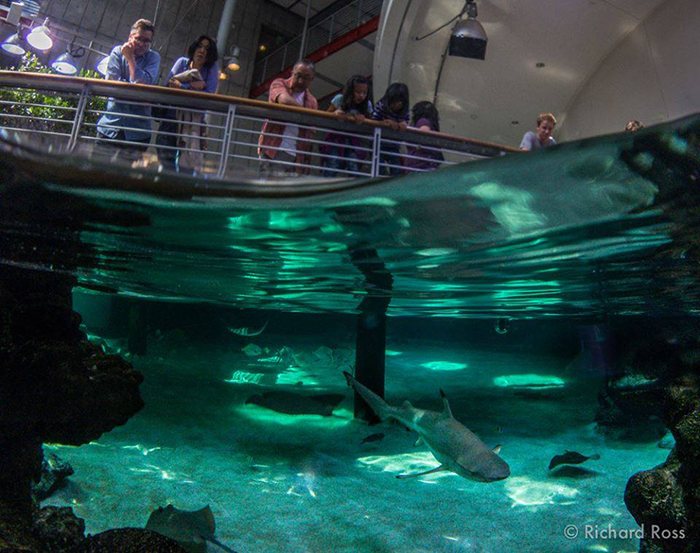

Everyone seems to agree that a brand new hobbyist shouldn’t purchase deep water fish, cephalopods, or non photosynthetic corals for their first tank, or that someone with a 50 gallon tank shouldn’t get a Blacktip reef shark, Giant Pacific Octopus or a Goliath Grouper. Besides obvious examples like those above (1), there is a huge grey area around what animals keepers should purchase and in which conditions it is appropriate to keep them in. Is it ok to keep a small tang in a small tank with the intention to transfer it to a larger tank when it gets bigger? How many fish is too many fish for a certain sized tank? No one has ever seen this fish before I better buy it before anyone else does! This situation is further complicated by the idea that there is a steep learning curve to keeping animals in glass boxes during that learning curve mistakes are made, and animals are lost. As a keeper’s experience goes up, they often start trying to keep more and more ”difficult” animals, and still there is a learning curve, and animals are lost – even to the best aquarist on the planet with the most resources. How do we cope with that idea?

Black tip reef sharks, have a small place – if any – in the hobby world. They need very large aquariums and vast amounts of food. Photo by Rich Ross.

Intent

Why animals stop living is important in regards to whether the loss is thought of as justified or abhorrent. Generally, people seem to accept losses when the aquarist has done due diligence as to the animal’s needs or potential needs, and has put enough time and resources into the animal and its captive habitat as to give the creature the best possible chance at survival. On the other hand, people that lose animals purchased on a whim, or who don’t really try to give the animal what it needs to thrive often are treated with scorn (though ironically, this may drive them away from helpful information and help them continue bad practices). Intent often makes the difference; if you really try, your efforts are worthwhile, even if unsuccessful, but if you don’t try, you are killing animals for no good reason. We seem to understand that part and parcel of keeping living animals in our homes is that there will be losses – this is unavoidable. However, as long as the attempt is made in good faith to avoid these losses, learn from them, and not repeat them, people generally feel that the endeavor has a net positive effect on the hobby. Moving through animals like they are cut flowers, buying compromised animals in bag lot sales because they are inexpensive, and not learning from those experiences is abhorrent to most people.

This Sepia bandensis cuttlefish is both captive bred and difficult to keep – should beginners keep it? Photo by Rich Ross.

Some people really put in the extra effort to share their experiences, both good and bad, via articles, blogs and forum posts, so that other people don’t have to reinvent the wheel by trying things that result in animal deaths. From this kind of information sharing we know lots of things that people don’t have to ever do again because they result in dead animals – try to raise cuttlefish on brine shrimp, open top tanks for flasher wrasse, treat ich with bananas, or try to keep non photosynthetic corals without feeding them (2). Since this information is readily available to anyone with a computer or phone, like the rest of this article may be a waste of time. Wait a sec, let’s unpack that a bit.

Everyone in the Hobby is on the Forums, so Everything is Cool

Whenever a discussion about ethics and the hobby arises, some are quick to say that most people in the hobby care very deeply about the animals, do research prior to buying anything, and do their best to make sure that that attitude is engendered in new hobbyists and that the “bad people” are a tiny minority. “Look at all the people on the reef forums” they say, “There are so many of them,” they continue, “there are only a few that don’t care enough to come here or read a book.”

When choosing a hard to keep fish, how far should the owner be willing to go to ensure its health? This Balanoperca pylei had decompression problems, and attempts were made to recompress this fish in a pressure chamber. Photo by Rich Ross.

While it certainly is the case that some people in the forums care, certainly not all of them do. After all, people supporting methodologies and disease treatments that have been shown to be ineffective are also on the forums, as are people that insist on keeping fish in inappropriate conditions (as evidenced by the tang police), or fish that they don’t know how to keep (as evidenced by the plethora of “I just bought an X, what does it need?” posts). To my continued dismay, threads on using ginger to treat marine ich, continue to have people championing its use – even though the idea has been shown over and over again to have no legs. Even if people on the forums care more than people not on the forums, it is important to understand that it is entirely possible that people on the forums may not actually make up the bulk of people in the hobby and that using the activity on the forums as a benchmark for the “average hobbyist” may be a “feel good” mistake.

Real data about anything in this hobby is hard to come by, so follow along on this line of reasoning that is based on what scant info we do have, some math, some good, old fashioned anecdote (4), and a generous helping of distancing qualifiers.

The best info that we have regarding the total number of salt water aquaria in the US comes from an often cited, but rarely seen (due to the 3000+ dollar fee to view it) American Pet Products Association (APPA) Pet Owners Survey (5). Though some are critical of the methodology of the study, it is one of the only sources of numbers that we have, and tells us that there are approximately 700,000 saltwater home aquariums in the US. Assuming that means 700,000 homes with saltwater aquaria (I know, assumption!) what we really want to know is how many of those people can be considered to be on reef forums, actively caring about doing the hobby the ‘right’ way.

Purchasing animals is always exciting, but supermarket shopping without forethought might be putting the animals at risk. Photo by Rich Ross.

I selected six US online reef forums (6), picking the largest I could find and some others that seem to currently have a decent level of activity. I added their total membership all together to get an overall number of people registered on reef forums in the US – 82,117.

For our purposes I left the high and low outliers because it gives us a bigger average membership number. Perhaps with all the cross membership between forums, the banned members, the duplicate, triplicate and dodeca accounts of banned members, the registered members that are no longer active, the one time posters, and the duplicate accounts of members with forgotten log ins, and non US members, this seems a decent number to estimate the number of actual living breathing people on forums in the US (how many times they post or the quality of their postings is another discussion). But lets be really generous, lets double the number, which gives us 164,234. Let’s be even more generous and round it up – 200,000 people on online saltwater communities in the US.

If, and that is a big if, those numbers are right, we have 200,000 people trying to do the saltwater hobby “right” and 500,000 people groping along in the dark, alone, with only their neighbors, Big Box pet stores and Tarot readings from which to get information. It looks as if the online forums are not the place where the bulk of people are getting their information about aquarium keeping. Clearly, further work on this topic would be illuminating, as would an analysis of the average length, depth and viewing of online reef discussions and the average length of time individuals stay in the hobby altogether.

Even Being on the Forums Doesn’t Equate to Being a Responsible Aquarist

Think back to your online favorite flame wars and ask yourself whether they had something to do with someone keeping an animal in too small a tank, or buying an animal they didn’t know how to care for, or about someone killing or letting an animal die but claiming they can “just get another one”. There are plenty of people that are part of online communities that embrace the “cut flower mentality” or only want to read ideas that agree with what they already think. Perhaps there wouldn’t even be any flame wars if there weren’t people adamantly and vigorously defending poor husbandry practices. While it seems that being a part of the online reefing community is better than not being a part of it, as it at least gets you closer to good information, I don’t think we should let ourselves fall into the trap of thinking that the forums have it covered in terms of good intentions regarding animals’ lives, or good advice regarding husbandry and disease treatment.

New Hobbyists and Captive Bred Animals

Probably the best animals for new hobbyists to work with are captive bred ones, because really, they only exist to be kept in aquaria. Wild animals are mostly a precious, limited commodity, so there is little reason for someone to cut their reefing teeth on animals pulled from the ocean and flown halfway around the world. Captive bred animals are already accepted for human use as food (burgers and feeder fish), experimental lab animals (mice, rats and cute fuzzy bunnies), or companionship (dogs and cats). This is not to say that captive bred animals suffering at the hands of new aquarists that don’t know any better is a good thing, but it is arguably more prudent than using a finite population of reef animals for the same purpose.

Captive bred fish like this Banggai cardinalfish, or designer clownfish are perfect for beginners since they were not taken out of the wild. Photo by Rich Ross.

Rescue Syndrome

One justification that people use for purchasing animals that they aren’t ready for, don’t know how to care for, or don’t have appropriate housing for, is that they rescued it from a store. Perhaps the animal was being kept in sub optimal conditions, was wounded, was slowly dying or starving, and the aquarist felt that the animal had a better chance in their home tank than in the store. Sometimes the animal is saved and goes on to thrive. More often, since the aquarist isn’t prepared for the animal or doesn’t even know what it needs to survive when healthy (never mind compromised), the animal doesn’t survive anyway. The worry here is twofold. Going from one bad situation to another isn’t much of a rescue, and if you purchase the animal that needs rescue, it seems you are likely training the store with the sub optimal conditions that those sub optimal conditions are acceptable, and they may continue doing what they were doing and continue to sell animals that are not healthy. If you are going to engage in rescue syndrome, I urge you at the very least to not pay for the animal so you don’t train the store to make a profit from avoidable situations.

While stunning this mimic octopus, Thaumoctopus mimicus, is only available wild caught, the status of its wild population is unknown, and it seems clear that this animal should only be obtained by individuals willing to give it the special care it needs. There is no reason to purchase this animal to ‘give it a try.’ Photo by Rich Ross.

How to Plan Your Animal Purchases

Ask yourself these questions, and encourage others to do the same, before purchasing any animal:

Is this an impulse buy?

Do you have enough experience to care for this animal?

Have you done basic research about this animal’s needs?

Are you buying this animal because it is cute, but don’t know anything else about it?

Are you rescuing this animal, but don’t really want it?

Can you provide consistent, good water quality?

Do you know what this animal eats? Live food? Can you afford to purchase the food for the life of the animal? Can you consistently obtain the food for the animal? Do you need to train the animal to eat a specific food?

Do you have QT space for the animal?

Is the animal photosynthetic? Do you have adequate lighting?

Do you have enough space for this animal? Will it fight with, eat or be eaten by other tank mates? Does it need its own aquarium?

Do you have enough time to devote to the care of this animal?

Not every animal is for everyone, and that is ok. We love these animals so, it seems like a good idea to be sure we know what we are doing, or at least have a good plan for keeping the animals, before we bring them home.

References/Notes

(1) As discussed in Skeptical Reefkeeping 7, some people feel that pet fish are really like cut flowers. After all, food fish are often kept in cramped and sub optimal conditions until they are killed to eat.

(2) Though of course, people still do all of these things.

(3) Ah referring to my own work – the ultimate argument from authority!

(4) One of the many references to the 2010 APPA study –http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/23/sc…anted=all&_r=0 . See alsowww.americanpetproducts.org

(5) Manhattan Reefs 5257, Reef2Reef 38482, Reef Central 257332, Nano Reefs 73747, Reef Sanctuary 46119, The Reef Tank 71765 – number taken from the membership sections of the websites August, 2014.

And special thanks to Jim Welsh for his help editing, proofing and finalizing this article.

0 Comments