Sphenopus marsupialis (closed, on left). Credit: Churaumi Okinawa Aquarium

The Churaumi Aquarium in Okinawa, Japan recently scored big with one of the most rarely seen and remarkable corals around. This giant polyp had until now never before been found in Japanese waters, and it has also probably never been put on public display until now. The zoas seen alongside this specimen should give a sense of scale, but what will likely surprise many is that this beastly creature is actually a solitary relative of the more familiar and colorful Zoanthus that abound in the aquarium trade.

Sphenopus is a small genus with just four species to its name, all of which live a solitary existence in sandy or muddy lagoons and flats. This is obviously in stark contrast to the colonial forms that make up the rest of this order, which tend to grow attached to hard substrates or in association with sponges or gorgonians. For these small, sessile animals, surviving in a sandy habitat is an impossible task, as they would quickly become buried under sediments. However, the larger and more motile Sphenopus can (like an anemone) adjust itself to maintain a position above the shifting sands of its environment. This has clearly been a successful strategy for this strange coral, and, while we seldom encounter them in the wild, they are presumably abundant within these poorly studied habitats.

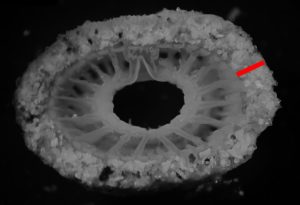

Sphenopus cross-section, illustrating the thick accumulation of sediment (red line) within the inner mesogleal layer. Credit: modified from Fujii & Reimer 2016

If you examine a cross-section of Sphenopus, you’ll very quickly notice that a thick layer of sand and silt is directly incorporated into the mesoglea, giving these animals a rigidity not seen in the floppy, gelatinous Zoanthus species. This trait is also shared with the genus Palythoa (commonly referred to as “palys” by aquarists), and it should come as little surprise that these two have proven to be each other’s closest relative. In fact, genetic study has strongly indicated that the solitary Sphenopus have likely evolved from within this genus, and they will almost certainly find themselves reclassified there in the near future.

Palythoa mizigama (left) & P. umbrosa (right, closed). Credit: modified from Irei et al 2015

Their closest Palythoa relatives appear to be a couple of recently described species (P. umbrosa & P. mizigama) that are unusual in the genus for being axooxathellate (i.e. non-photosynthetic) and forming small colonies within caves and crevices. While these drab and innocuous creatures might not appeal to many aquarists, they are a fascinating group for those interested in the evolutionary history of this diverse lineage of corals. No doubt, the path that led from the colonial, photosynthetic reef species to the solitary and azooxanthellate Sphenopus required an ecologically intermediate form such as that seen in these two cavernicolous species.

Sphenopus marsupialis is a bashful beastie. Credit: Churaumi Okinawa Aquarium

There’s not much recorded regarding the husbandry requirements of Sphenopus. The single polyp of S. marsupialis at the Churaumi Aquarium was noted in Reimer et al 2016 (pdf) to open at night, though it was apparently seldom seen to expand fully expand. There’s no mention of what, if anything, it fed upon, though it can be assumed that chopped meaty foods would be accepted in the same manner as in other species of Palythoa. This specimen clocked in at an impressive 5cm in diameter and 9cm in height, which is, of course, stupid big for a zoantharian. An earlier study by Soong et al 1999 reports that this species is capable of reproducing both sexually and through asexual transverse fission. In larger specimens, a constriction can form across the midline of the body (visualize the hourglass shape of a peanut) which will eventually fully divide the organism into two—the process is said to take a couple weeks to complete. This is promising should this species ever be collected for the aquarium trade, as a single individual could in theory create a sizable number of individuals through this self-fragmentation. These researchers also mention that specimens kept for long periods in aquariums produce relatively clear tissue if there is no sediment to incorporate into their bodies. This too has interesting potential for aquarists, as their coloration is seemingly dependent on whatever substrate they are kept upon. Therefore, if Sphenopus were to be cultured on pink sand, you would produce pink Sphenopus!

Sphenopus marsupialis, in all its glory. Credit: Churaumi Okinawa Aquarium

It’s a shame that there isn’t more interest on the part of aquarists for unusual corals like this. Sphenopus is an incredible creature which would likely be simple to keep and which could easily be collected if there was demand for it… but, since these humble polyps aren’t quite so gaudy as some of the truly popular designer corals in the aquarium trade, we’ll likely never have the chance to enjoy it. I, for one, would gladly take a Sphenopus over a “Bounce Mushroom” if anyone would be so kind as to collect one.

0 Comments