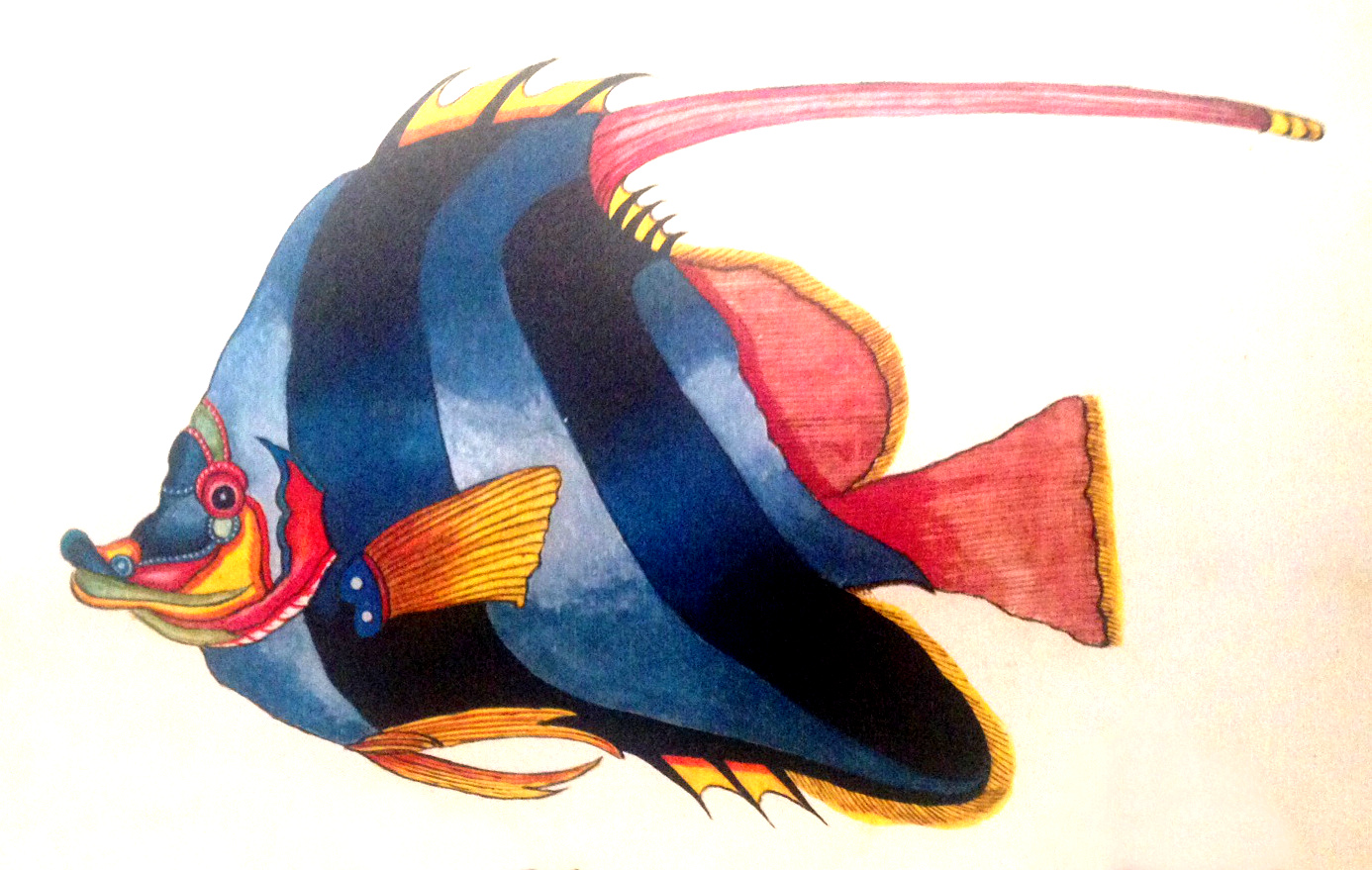

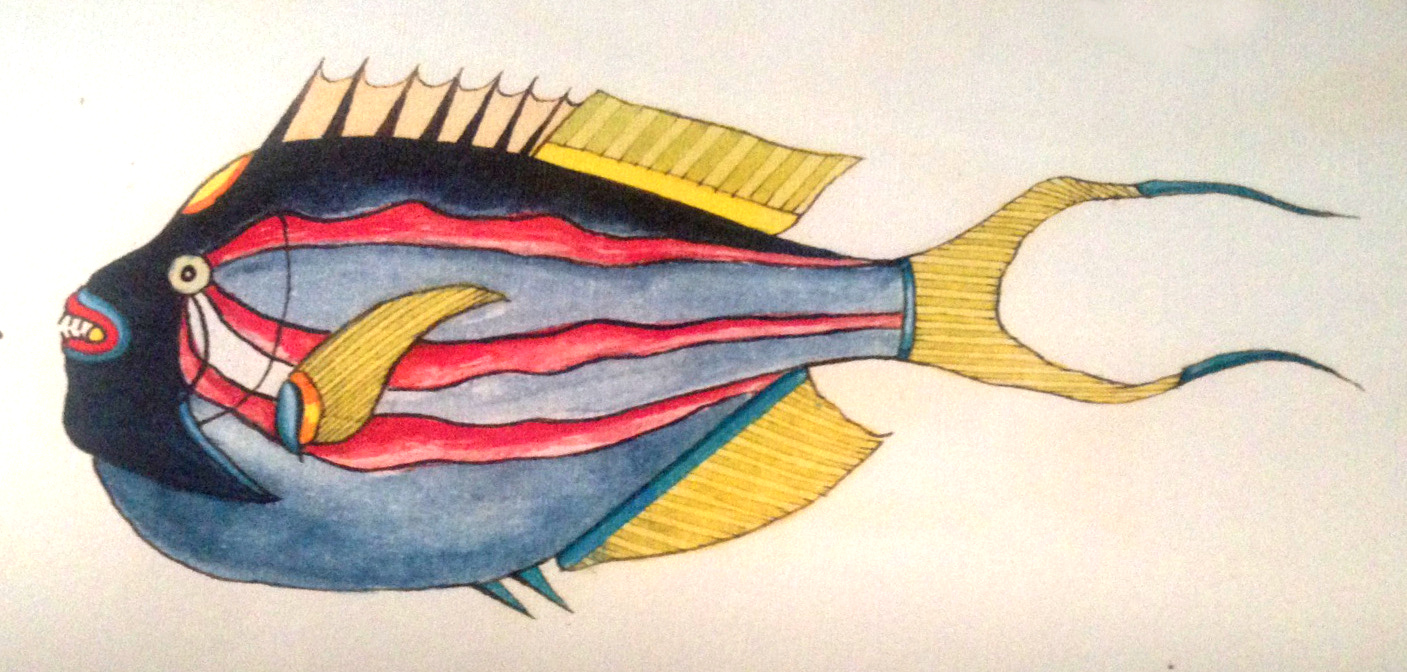

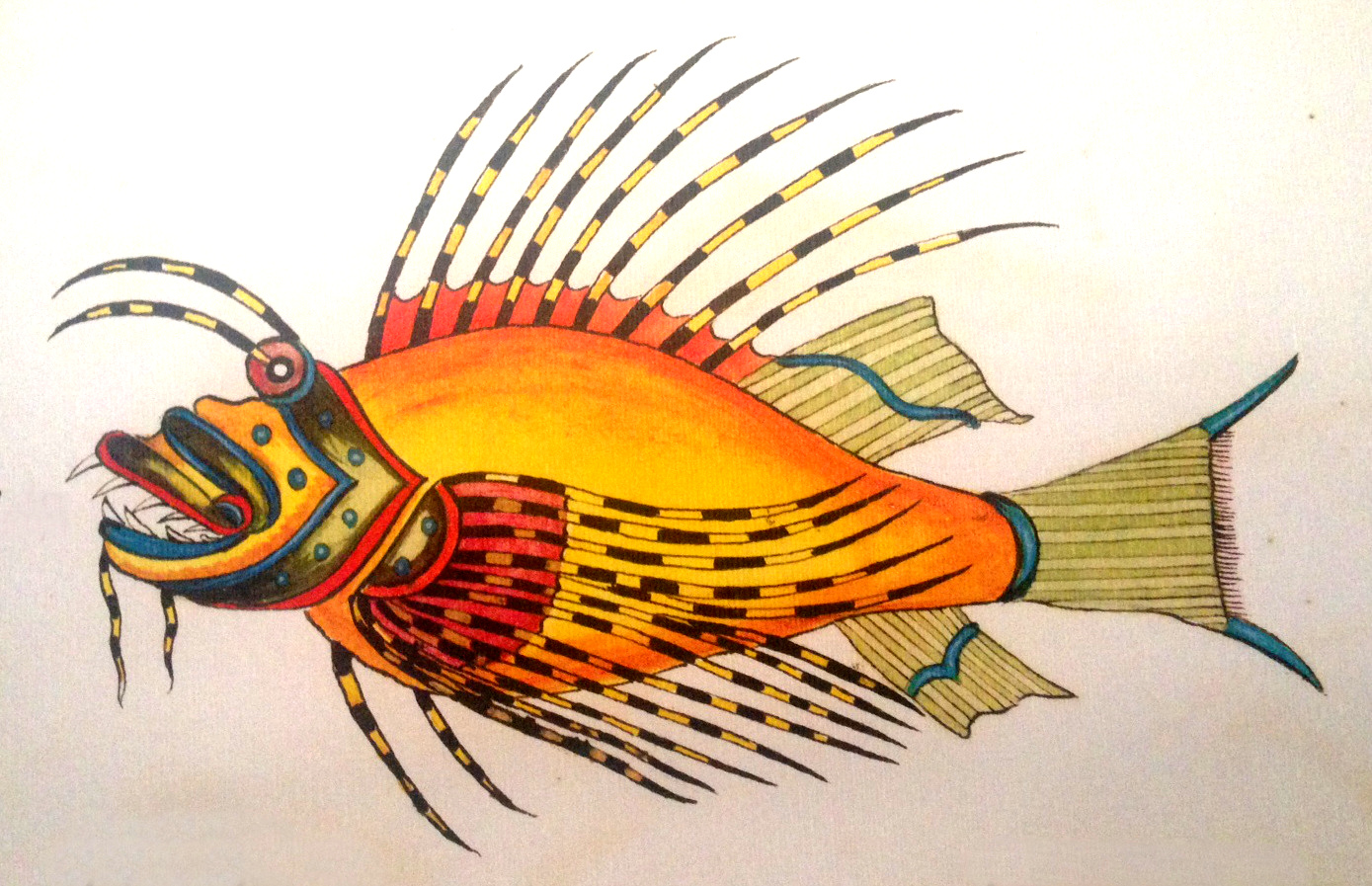

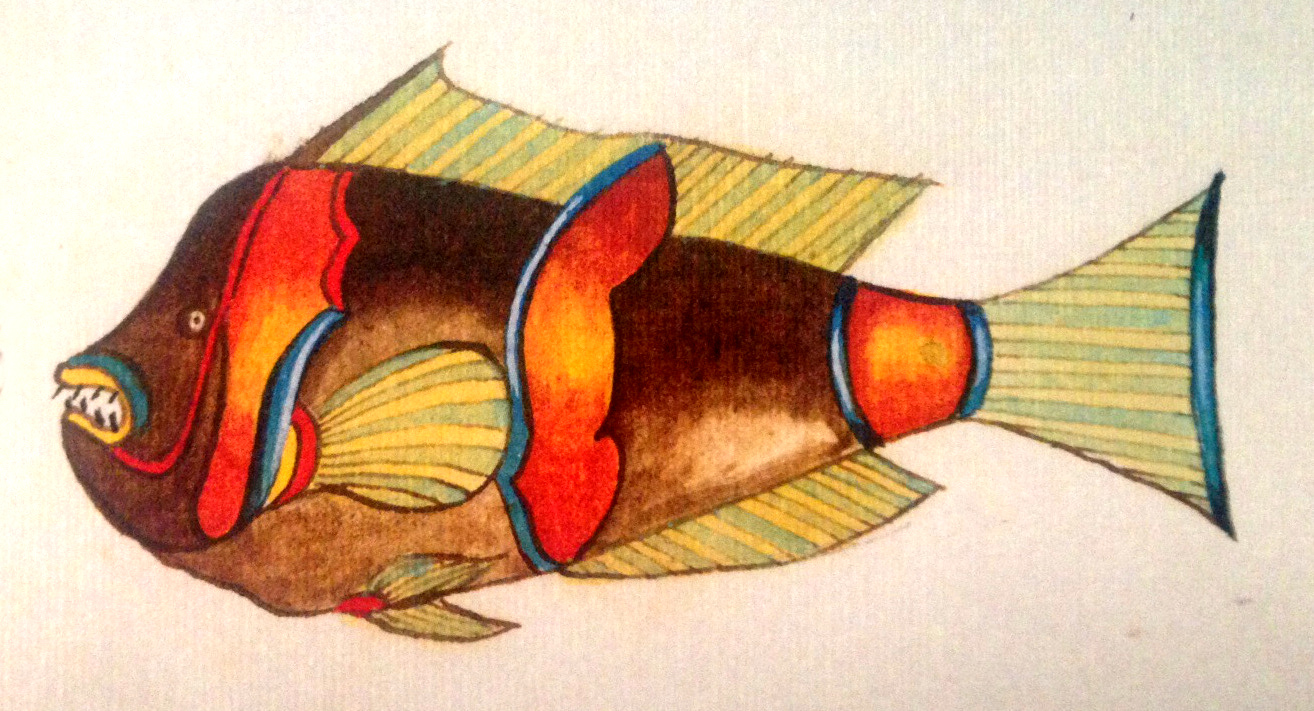

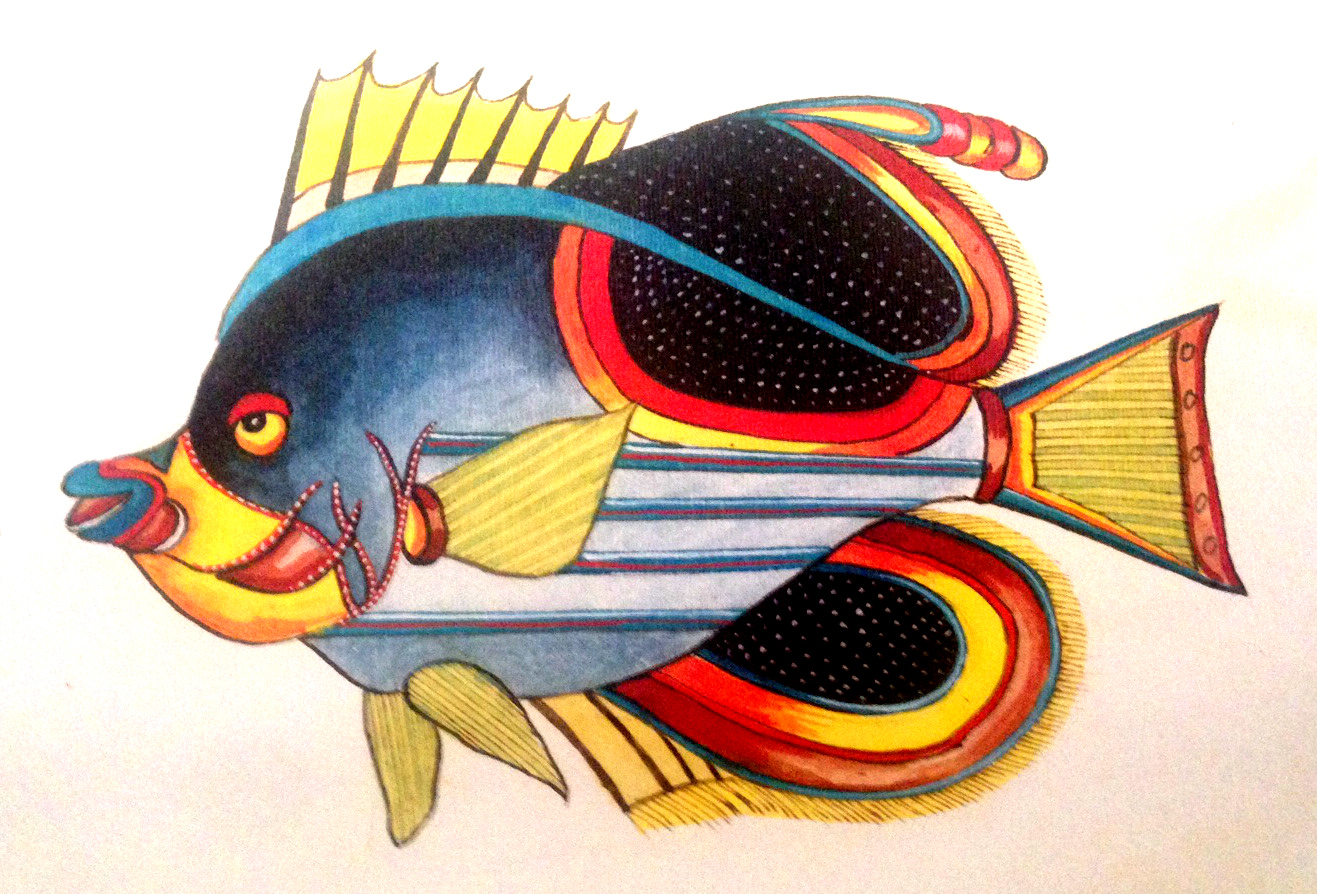

Because of this judicious use of artistic license and the general unfamiliarity an early 18th-century Dutchman would have had regarding the reef fishes of Indonesia, an effort had to be made on the part of Renard to verify the legitimacy of the work he was about to publish. To this end, he acquired a written affidavit from Samuel Fallours, who stated, “I declare that the fishes included in this collection were drawn and painted by me from nature. This was done to the best of my ability, not believing that the human arts can express the beauty of the colors of these fishes when caught alive…”

Still, we have reason to question the truthfulness of Mr. Fallours, for alongside his illustrations were brief accounts of these creatures which don’t exactly corroborate well with what we now know about their biology and life history. Take, for instance, the notes which accompany the Spiny Lobster stating that it lives in the mountains, where it climbs trees to eat fruit, that it dislikes snakes, and that it lays red-spotted eggs the size of a pidgeon’s. And what of the story concerning how he kept a pet frogfish (Antennarius spp.) alive in his home, out of water, for three days, and that it followed him around like a puppy. And then there’s the yarn about the pipefish which whistles loudly and can be folded like a handkerchief and put in one’s pocket, only to unfold to its former shape when removed.

And then there’s that damn mermaid. It would be easy to discount this as nothing more than the bemused scribbles of a mad Dutchman, but Fallours claims that a living specimen was actually brought to him by local fishermen, purchased for “two ells of cloth”, and subsequently kept alive for precisely four days and seven hours. He goes on to report that it was capable of making mouselike noises and moving its face in the same manner as a cat’s. He attempted to coax this creature into feeding in captivity, but, alas!, to no avail. This poor, unfortunate “woman of the sea” ultimately succumbed to her unwillingness to eat. If only Mr. Fallours has known to add garlic and Selcon! Ever the assiduous scientist, he inspected the body, gently lifting up the fins which had in life hidden the naughty bits below the waist, verifying beyond any doubt that this was indeed an actual merperson, with all the anatomical ladyparts one would expect.

Samuel Fallours’ lived in Ambon from 1706-1712, painting fishes whilst in the employ of the Dutch East India Company. When he was eventually made to relocate elsewhere, he becomes lost to history. His artistic genius, his mastery of ichthyological illustration, was cut far too short. But his legacy lives on in the kaleidoscopic prints which have survived into the present day. While you may never have the opportunity to own an original copy of his work, a beautiful reproduction has recently been published by Taschen. Rather than an exact copy, this collection focuses exclusively on Fallours’ fishes, leaving out the original Dutch annotations and instead focusing solely on their aesthetic qualities. Given his importance to the history of coral reef science and natural history illustration, it’s surprising that there is not a single species which has been named in his honor. Perhaps now that Samuel Fallours’ name has finally been brought to light after centuries of obscurity, he can at last be recognized for the originality of his contributions to marine science.

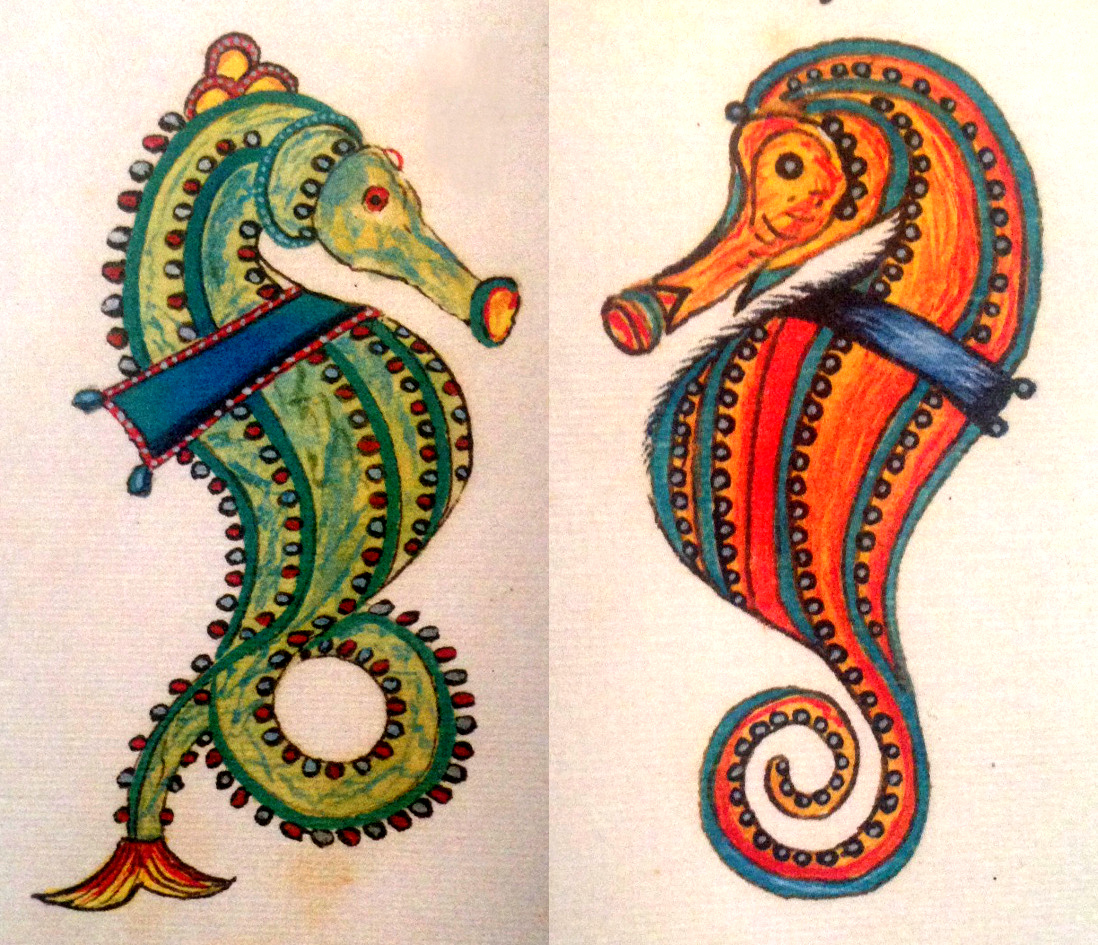

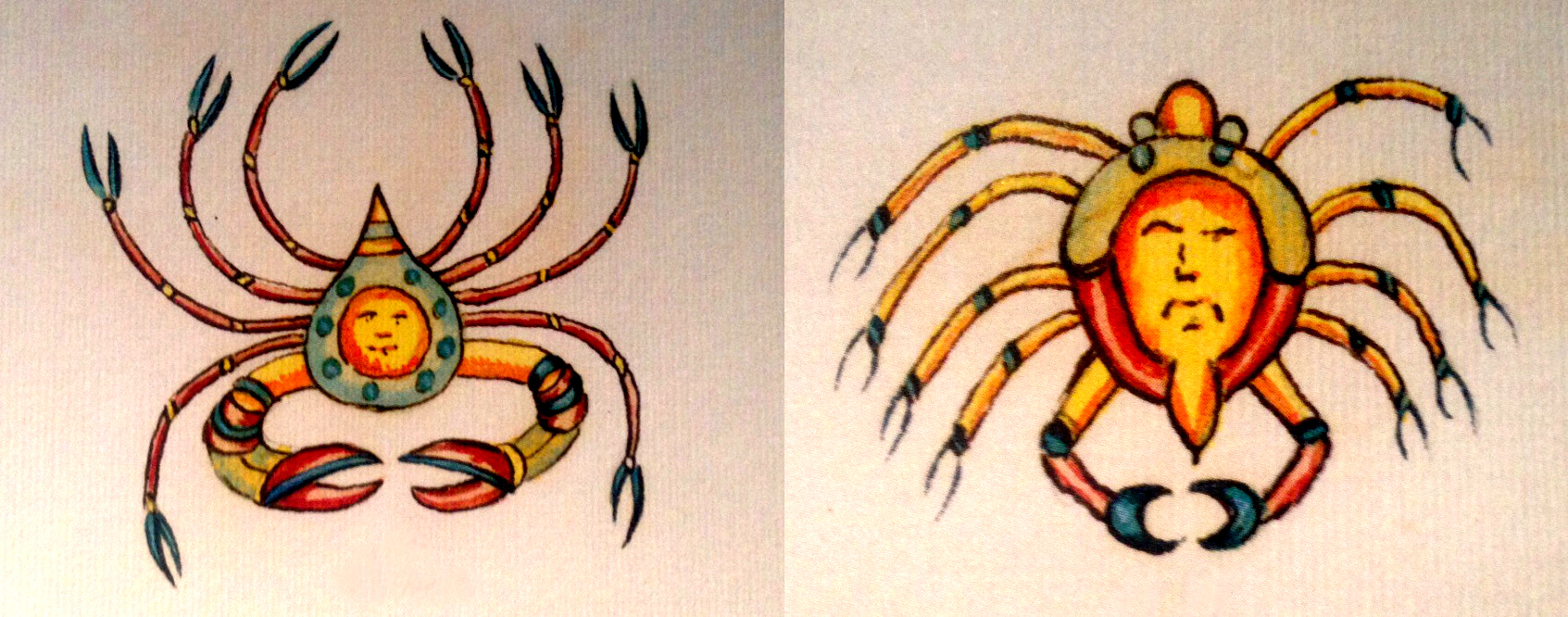

These fanciful creatures are said to represent a parasitic isopod, Mothocya renardi, named for the publisher of this book, Louis Renard.

0 Comments