The Blacktail or Old Woman Wrasse, Thalassoma ballieui, at Hanauma Bay, Hawaii. Credit: Bill Stohler

The genus Thalassoma is comprised of a diverse assemblage of large, reef-associated wrasses spread throughout the world’s tropical and subtropical waters. Included here are some of the most familiar, colorful and active labrids available to home aquarists—the Lunare Wrasse (T. lunare), the Banana Wrasse (T. lutescens), the Bluehead Wrasse (T. bifasciatum), and the unusual Bird Wrasses (“Gomphosus”). Aside from a handful of species with highly restricted distributions, most every species is regularly offered in the aquarium trade, but this isn’t so for the two most “primitive” members of the genus…

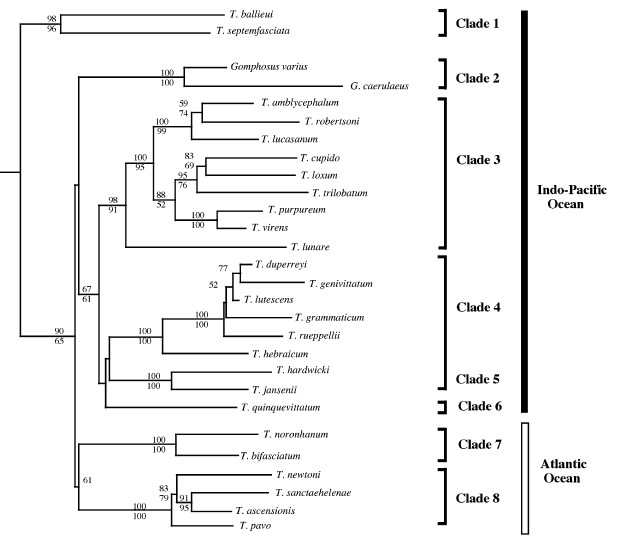

Phylogenetic relationships of Thalassoma. Source: Bernardi et al 2002

Unlike most wrasses, Thalassoma has been fortunate enough to have had its evolutionary history well-studied thanks to the genetic study of Bernardi et al 2002. This led to several interesting and rather unexpected conclusions, such as a deep division in the genus between Atlantic and Pacific taxa, as well as the strong support for including the “Gomphosus” Bird Wrasses as close relatives of the more traditionally shaped members of the group. But the finding which most intrigued me relates to the peculiar biogeographic mystery surrounding the earliest lineage to split off, as this basal clade includes a pair of species endemic to the isolated reefs of Hawaii and Western Australian—two fishes that look little alike and are separated by a vast stretch of ocean.

The Hawaiian species is T. baillieui, known variously as the Blacktail Wrasse or the Old Woman Wrasse. The latter name seems a bit unfair to this poor fish (and perhaps a bit sexist too), as it makes light of the rather drab colors sported by the species. While the juveniles are a lovely chartreuse, adults become increasingly muted, with males maturing into an understated grey vestiture. Aside from its chromatic deficiencies, this fish suffers from the rather monstrous proportions it’s capable of reaching, with a maximum size of well over a foot in length. And, as if that weren’t enough to make this fish unpopular, it’s also quite seldom seen within the common collection locations of the Hawaiian Islands, being more abundant in the cooler waters of the northwestern portion of the archipelago. This is decidedly not a fish one sees in many aquariums.

The Seven-banded Wrasse, Thalassoma septemfasciatum. Credit: Barry Hutchins

The same can be said for its Australian sibling, the Seven-banded Wrasse (T. septemfasciatum), which is restricted to the subtropical algae-dominated reefs in the southwestern corner of the continent, from Ningaloo in the north to Perth in the south. As aquarium collection does take place to some extent here, it’s possible the occasional specimen has trickled into the trade, but, if so, there doesn’t seem to be any record of it. This is another rather aesthetically depauperate and underwhelming piscine—a labrid non grata, if you will. Females come adorned in a series of oblique cream and brown vertical bands, while males develop a more stately caerulean hue, replete with some vividly contrasting yellow pectoral fins.

A mature male Thalassoma septemfasciatum. Credit: redemperor000

The lineage that led to these two fishes is said to have diverged from the rest of the genus somewhere around 8-13 MYA, suggesting that there was once a more widespread and diverse assortment of subtropical species which has been reduced over time to this last pair of evolutionary survivors. This can be inferred by the considerable geographic disjunction which serves to separate these two populations, as well as the obvious differences in their appearance and the relatively deep genetic divide which separates them in the study of Bernardi et al. So, while these may be “sister species”, they’re really more like distant cousins from a family which has mostly died off.

Female Thalassoma septemfasciatum. Credit: Shortly

I’ve always had a bit of a soft spot for phylogenetic relicts such as these. While one group of Thalassoma blossomed and diversified into the lovely, colorful fishes so adored by aquarists, another trudged on in an altogether different and less successful direction, ultimately diminishing over time due to the vagaries of natural selection. With the oceans warming, they may not be long for this world, but there’s still something admirable about their fortitude and endurance in the face of so much evolutionary adversity, like the last runner to cross the finish line at a marathon. Other groups have their own version of this—Laboute’s Fairy Wrasse, the Latezonatus Clownfish, Thompson’s Surgeonfish. These survivors offer a window into the history of the ocean, and, if placed together in an aquarium, could make for a truly unique Miocene biotope.

0 Comments