The colorful deepwater basslets of the genus Lipogramma just welcomed a pair of new species into their ranks. Though unfamiliar to most, these lovely little fishes are one of the true holy grails for aquarists, with specimens tending to fetch a small fortune relative to their miniscule proportions. But, as it turns out, we’ve been misidentifying one of these species for quite some time.

In total, there are now ten recognized species in the genus, though only three are collected with any regularity. Of these, arguably the most attractive is a black and white species which has been identified by aquarists as the Banded Basslet Lipogramma evides. This fish ranges throughout the Caribbean, with aquarium specimens originating from Curaçao. It was here that researchers from the Smithsonian boarded the famed Curasub and acquired specimens which lead to a surprising discovery… there are, in fact, three species of dark-banded basslets.

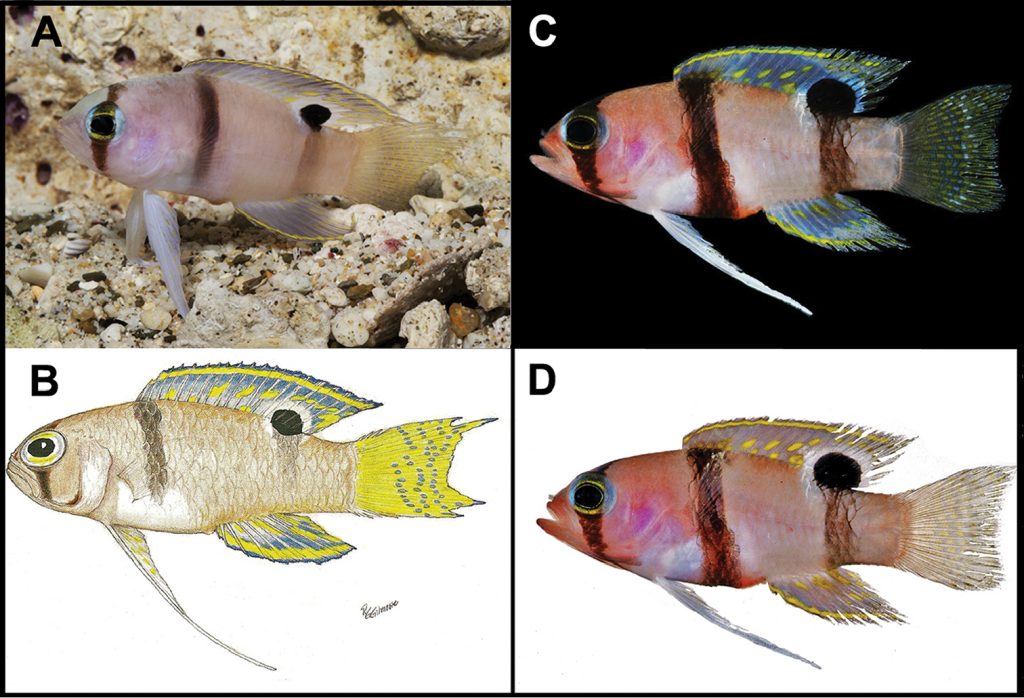

The fish which we have been calling L. evides is in fact a smaller and more shallowly occurring relative which has now been described as the Hourglass Basslet Lipogramma levinsoni. The common name alludes to the distinctive appearance of this fish’s dark bands, which are somewhat thickened dorsally and ventrally, creating an hourglass-like shape. In comparison, the true L. evides has noticeably thinner and more evenly-shaped bands. The dorsal fin also differs subtly, with L. levinsoni having an orange submarginal stripe, whereas L. evides has a yellow stripe with several yellow spots that are absent in its piscine doppelganger.

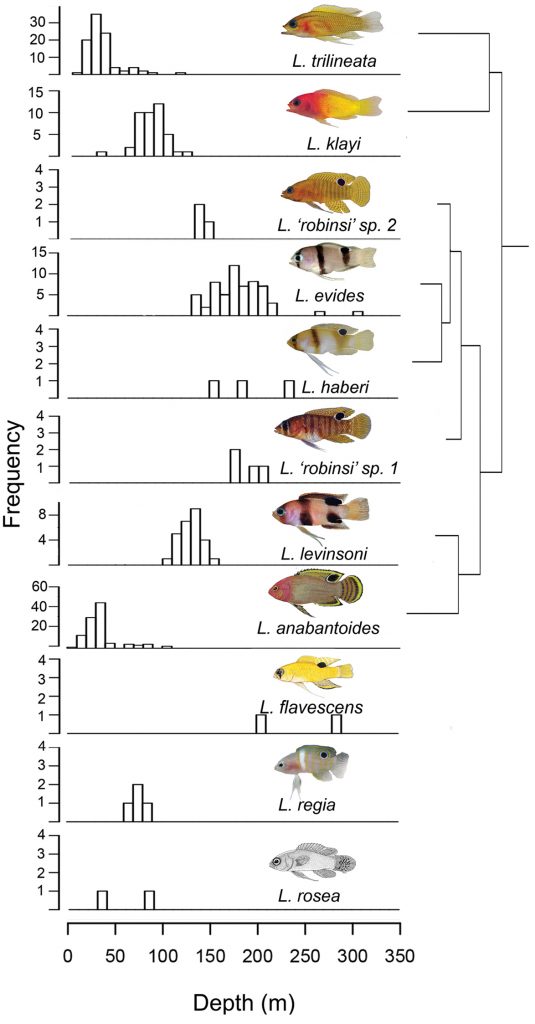

There are also several morphological differences, such as differing gill raker and pectoral fin ray counts, as well as an extra sensory pore above the eye. But the most relevant trait for aquarists is the considerably smaller maximum size of L. levinsoni (28mm) compared to the true Banded Basslet (45mm). As a quick Google search confirms, the vast majority (possibly all?) of the specimens seen in captivity are the Hourglass Basslet, though both species have been collected by the Curasub and are liable to appear. In the wild, L. levinsoni occurs in somewhat shallower waters, preferring depths from 108-154 meters, while the Banded Basslet ranges deeper, from 152 to 300 or so meters.

Interestingly, genetic data indicates that these two basslets are not each other’s closest relatives. That honor instead goes to another newly recognized fish—the Yellow Banded Basslet Lipogramma haberi. Unlike its banded relatives, which are known from scattered locations throughout the Caribbean, this species is thus far only recorded from the tiny island of Klein Curaçao, located just southeast of Curaçao, in depths from 152-233 meters. Unlike its black and white brethren, L. haberi is instantly recognizable on account of its yellower color along the back and the brown hue of its bands. Hinting at its close relationship with L. evides, the Yellow Banded Basslet has a similarly patterned dorsal fin, with a yellow submarginal stripe and numerous yellow spots.

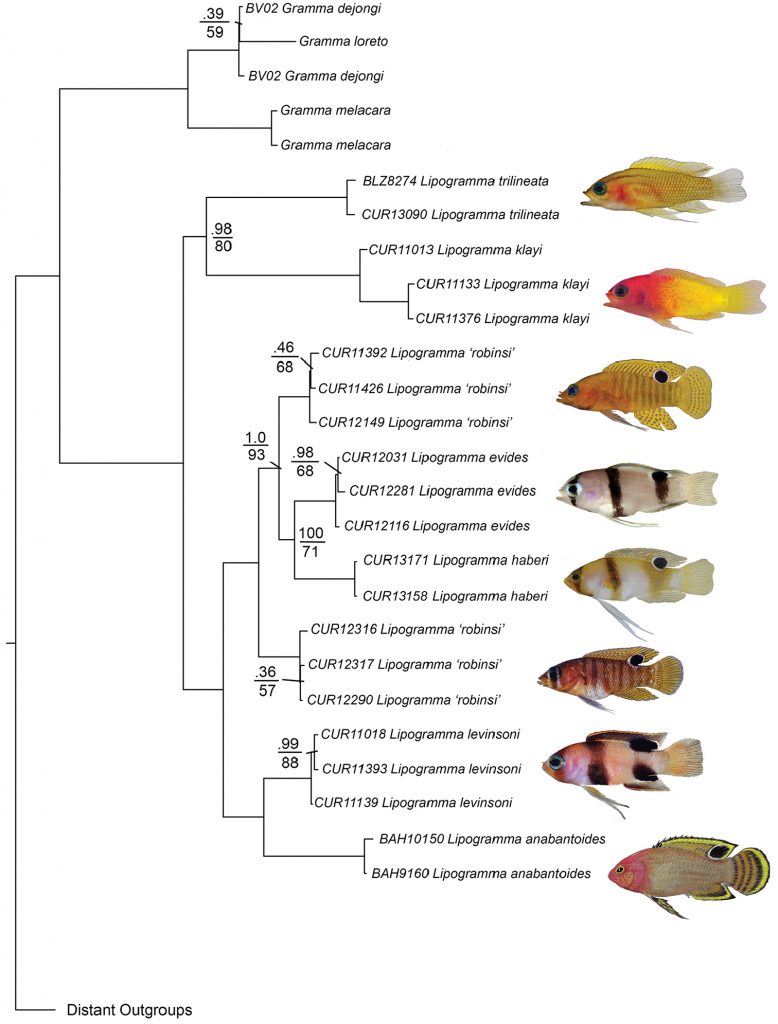

The authors include a phylogenetic tree, giving us some insight into the processes that have allowed these little fishes to speciate so abundantly in the Caribbean. The group divides neatly into two clades that can be diagnosed by the presence or absence of a large black spot in the dorsal fin. Among the half-dozen species possessing this maculated dorsal fin, there is evidence to suggest that the relative depths favored by these fishes has encouraged their diversification.

Still, we know quite little concerning the natural history of these species and how they differ from one another. A few scant observations are reported: L. levinsoni tends to occur in pairs; L. evides feeds on the foram Globorotalia manardii; L. levinosni feeds on a diatom (Coscinodiscus eccentricus?). But one can’t help but wonder, why are there so many basslets lurking in the mesophotic reefs of the Caribbean. What nuances of their behaviors and biology keep one species from outcompeting another? Given the challenges associated with studying these fishes in their natural habitat, it may be a while before we have answers to these most basic of basslet questions.

Baldwin CC, Robertson RD, Nonaka A, Tornabene L (2016) Two new deep-reef basslets (Teleostei, Grammatidae, Lipogramma), with comments on the eco-evolutionary relationships of the genus. ZooKeys 638: 45-82. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.638.10455

0 Comments