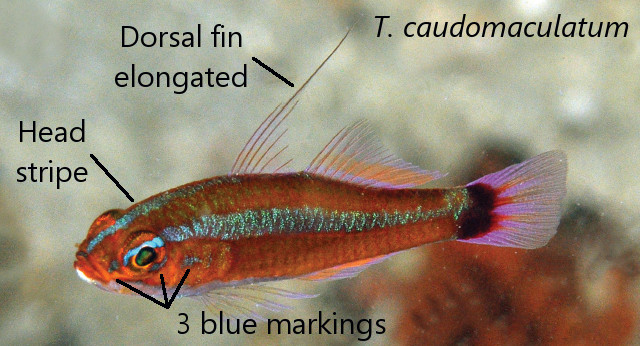

The Blotch-tailed Pygmygoby (Trimma caudomaculatum), seen in the usual upside-down swimming posture. Credit: Klaus Stiefel

The genus Trimma is a vast and challenging group of tiny reef-associated fishes (known variably as pygmygobies or dwarfgobies), with perhaps as many as 200 species, many of which still await scientific description. Though they are ubiquitous on Indo-Pacific reefs, relatively few species make their way into the aquarium trade, even though they are often highly colorful and perfectly suited for life in smaller aquaria. One of the most frequently seen members of this group is a blue-striped fish identified as Trimma tevegae and which goes by an endless variety of common names: the Blue-striped Cave Goby, the Bluestripe Pygmygoby, the Bluestripe Dwarfgoby, the Blue Line Flag Tail Goby… and on and on and on. As it turns out, we’ve been identifying this fish incorrectly.

In 2014, Winterbottom et al published a study examining the genetic relationships of this genus, finding evidence for numerous “cryptic species” in the T. tevegae group that were in need of further study, and, now, in the latest edition of Zootaxa, he has finished this work by describing three new species. What’s particularly surprising about this discovery is just how genetically distinct these are from one another, despite their near identical appearance.

The true T. tevegae, seen here with T. nasa in the Philippines, is a drab fish that lacks a stripe on its head and has a thick line through the top of the eye. Credit: Klaus Stiefel

In many groups of reef fishes, we would expect closely related species to have only minor differences in their mitochondrial CO1 gene (the so-called “DNA barcode”), with anything greater than a 2% difference being deemed distinct enough to warrant recognition as a separate species. Some familiar groups (Pseudojuloides, Xiphypops, Cirrhilabrus) buck this trend entirely and have species complexes that differ dramatically in appearance and biogeography while still showing identical genetics in the CO1 gene. But with the Trimma tevegae complex, most species differ by a whopping 8-10%, about what we might expect to find when comparing different genera! And for the newly described T. corerefum, the difference between it and its relatives was a staggering 20-22%. This might relate to the relatively short lifespan these tiny gobies have, often no more than a few months in the wild. With such a quick reproductive turnover, there is far more potential for genetic changes to accumulate relative to a longer-lived reef fish (such as an angelfish or surgeonfish, which can live for decades).

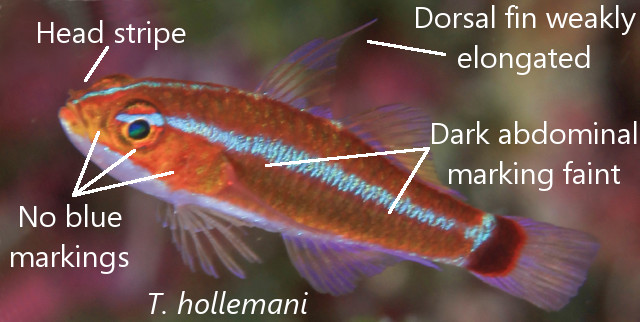

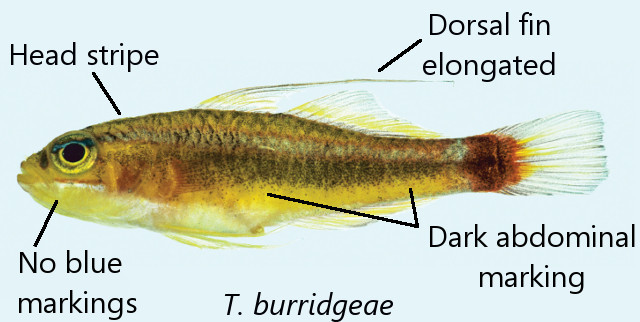

The images I’ve included here illustrate some of the more readily recognizable diagnostic traits for identifying these fishes from photographs (others are discussed in Winterbottom 2016). The presence or absence of a blue stripe along the snout is the most salient trait and serves to distinguish the stripeless species (the true T. tevegae and T. corerefum) from those with a stripe (T. caudomaculatum, T. hollemani and T. burridgeae). Other useful features include the relative length of the dorsal fin spines in mature males—the group is sexually dimorphic, with females usually having short fin spines— and the details of the blue facial markings. Still, not every species is easily identifiable, as T. hollemani and T. burridgeae are highly similar in appearance.

https://youtu.be/IP0awCqy934

Holleman’s Pygmygoby (T. hollemani) is the most abundant species in the aquarium trade. Credit: Quality Marine

In researching this discussion, I examined a large number of aquarium specimens to see which species is being collected and exported, and, sure enough, Trimma tevegae is not to be found. In fact, this species is seemingly quite uncommon in general, with few instances of it being documented by divers. This might have something to do with it being reported from relatively turbid inshore waters, rather than the clear oceanic habitats favored by related species. The majority of the specimens seen in the aquarium trade are apparently Holleman’s Pygmygoby (T. hollemani), a widespread species in the West Pacific. Also seen (albeit more rarely) is the Blotch-tailed Pygmygoby (T. caudomaculatum), which differs from the previous species in having several distinctive blue markings present on the head and for tending to have more vibrantly colored fins. The length of the elongated male dorsal fin spine is also considerably longer in this fish.

This specimen, seen in Palau at 15 meters, may be the first photograph of a live T. burridgeae. Credit: taku-chan

There is still a great deal left to study with this group. We as yet have only a cursory understanding of where these fishes are found. Why, for instance, is T. burridgeae only known from Palau—is it a Micronesian endemic with a greater range to the east? There’s also some genetic evidence to suggest that T. caudomaculatum, which is thought to be the most widespread of these gobies, ranging from the Maldives to the West Pacific, might actually be a species complex of its own. And what ecological specializations have allowed so many species to live together in this region? Do they directly compete with one another for food and habitat? Thanks to the efforts of Dr. Richard Winterbottom, goby authority par excellence, we are a bit less benighted when it comes to these beautiful little beasts, but we clearly have much left to learn.

- Winterbottom, R. (2016): Trimma tevegae and T. caudomaculatum revisited and redescribed (Acanthopterygii, Gobiidae), with descriptions of three new similar species from the western Pacific. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4144.1.8

0 Comments