The genus Sarcophyton is comprised of several soft corals belonging to the Subclass Octocorallia and Order Alcyonacea. Depending on where you look, there are between 41 and 46 species altogether (ex. Aratake et al., 2012 & WoRMS, undated), with all of them being commonly known as toadstool corals. The name comes from the fact that they look much like large toadstool mushrooms, and they’re generally fast growing and hardy corals, too. They can also be easily propagated by cutting, all in all making them a good choice for aquarists looking for an attractive and oftentimes large addition to a reef aquarium. So, I’ll give you some good information about them.

To start, toadstool corals usually have a rounded trunk that stays firmly attached to the substrate. This trunk can be relatively tall and slender compared to the size of the whole, but may also be rather short and fat to non-existent depending on the species and size of a particular specimen. This trunk is topped by a generally rounded and typically flattened cap called a captitulum, although the capitulum often becomes rather ruffled or folded when some species grow to a large size. This does make them look much like an aquatic toadstool mushroom though, and makes it easy to see where these corals got their common name from. These are also called toadstool leather corals at times, as their body has something of a wet leather-like feel and is relatively stiff for a skeleton-less coral. This is in part due to the presence of numerous tiny hard carbonate structures called sclerites, which are found throughout them.

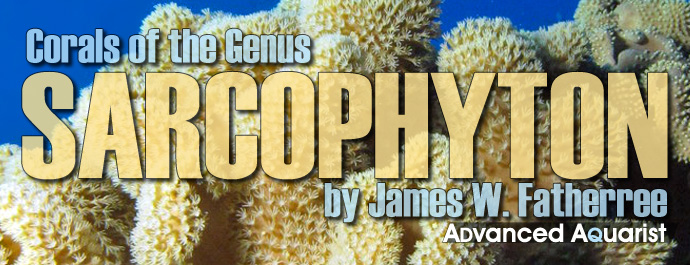

Regardless of overall form and feel, toadstools have numerous polyps that arise from the capitulum, oftentimes being long and slender and waving back and forth in currents. Here again there is some variability though, as some have long polyps possessing relatively large tentacles, while others may be rather short and/or have tiny tentacles at their tips, or anything in between. And, unlike those of stony corals, the tentacles are pinnate with each being lined by small branches that can make them look much like little feathers.

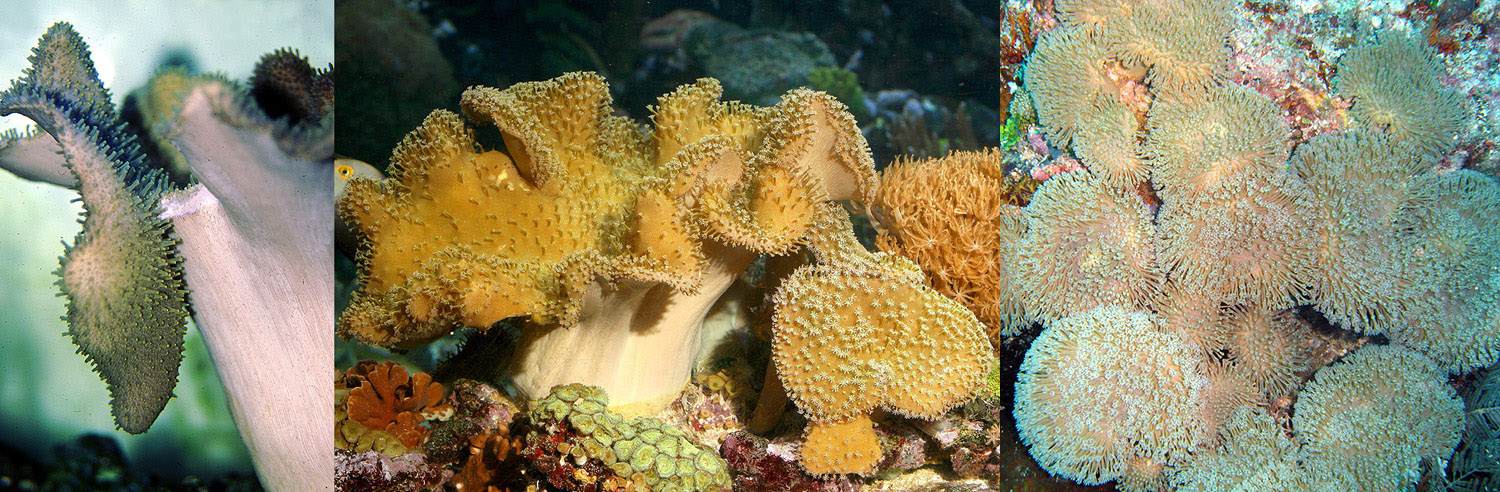

When it comes to coloration, toadstools are most commonly cream to light brown, but may also be green, pinkish, or yellow. The base/stalk of the polyps that emerge from the capitulum may be the same color as the rest of the body, or sometimes a bit darker, but the tentacle-bearing tops of the polyps frequently have different colored tips/tentacles. Typically they’re much lighter in color, being light cream, white, or rarely light blue, providing some contrast and making many specimens especially attractive.

While the majority of toadstools are cream to light brown in color, there are other colors available.

Regardless of coloration, do note that a toadstool’s polyps won’t always be out, though. The capitulum is dotted with little pores that the polyps can retract down into, so there are times when it may be smooth looking and apparently polyp-free. In fact, it’s common to see the polyps fully expanded during the day/when the lights have been on for a while, and then completely retracted within the capitulum at night. If a specimen is in good health, the polyps will emerge regularly though, which is often called “polyping out”, and won’t stay hidden long-term. There may be a period when they stay retracted for several days when first introduced to an aquarium, but once a specimen has settled in you should observe the coral’s very slow polyping out reaction to the aquarium lights being turned on in the morning.

Still, there’s an odd exception. Toadstools can also produce a waxy coating that usually covers most of the coral, but is especially thick on the capitulum. This is normal behavior though, and the coating is generally thought to be a mechanism to remove any unwanted detritus that has settled onto a specimen, or algae that has grown on it. The coating is typically sloughed away after a few days, allowing the polyps to emerge.

While in most cases this seems to be a harmless process, on occasion it has been observed that the coating material can strongly irritate other corals that it may come to rest upon in an aquarium. So, it’s a good idea to watch closely and when a toadstool begins to shed its coating you should net and remove any bits and pieces that you can.

In the event that the polyps won’t emerge for long periods, or a coating won’t slough away after several days, you can try moving the specimen to an area where the lighting and/or current is different. While toadstools can thrive under intense lighting, it is possible to “light shock” a specimen if it has been under relatively low-intensity lighting for some time and is then put right under something much, much brighter. A specimen can adapt to an increase in lighting, but it can take time. Likewise, water flow to be inappropriate, so you can use some judgment and try a different spot where the current is stronger or weaker depending on the situation. In my experience, a change of current is typically all it takes to get a positive response from non-responsive polyps, unless a specimen is really in poor health after collection, shipping, and handling.

At times a toadstool may retract its polyps and take on a rather shriveled up look. This is not unusual though, even when healthy and growing, and they typically “recover” from such states within a few days unless there’s a real problem.

However, I do have to add that over the years I’ve come across a couple of toadstools that kept their polyps retracted no matter what. Even in exceptionally well-maintained tanks, there are such times when a healthy, growing specimen has just refused to polyp out. This is uncommon though, and is likely a sign that it is being stung or irritated by another coral(s). I’ll say more about this momentarily.

Some hobbyists have also reported that the use of phosphate-removing products that contain aluminum can have strongly adverse effects on a variety of soft corals, including toadstools. Apparently some phosphate removers release aluminum into the water, and if concentrations get too high, specimens may retract their polyps and shrivel up. So, if such a product is used and a previously healthy-looking toadstool starts to look bad, this might be the reason. Take a look at Holmes-Farley (2003) for more on this.

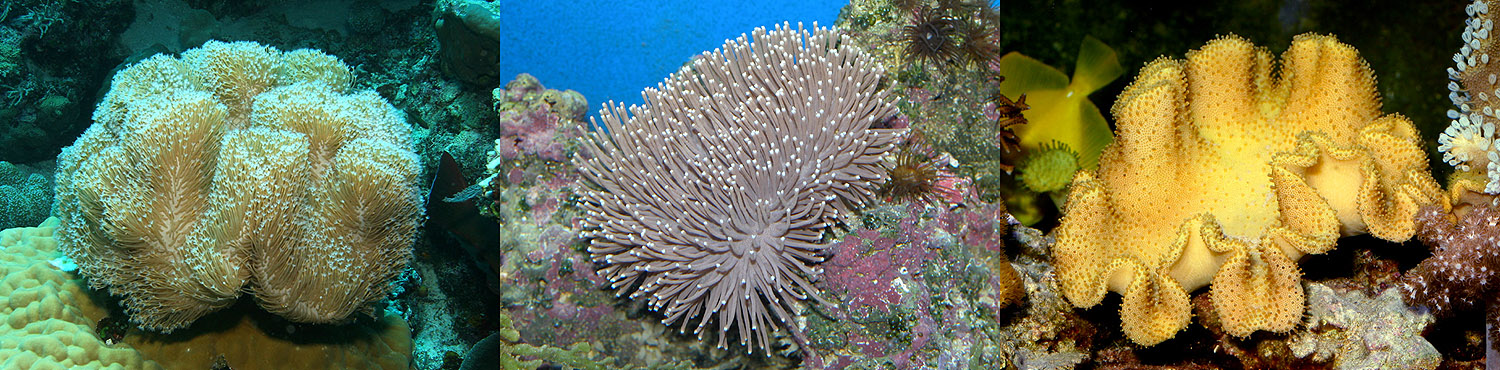

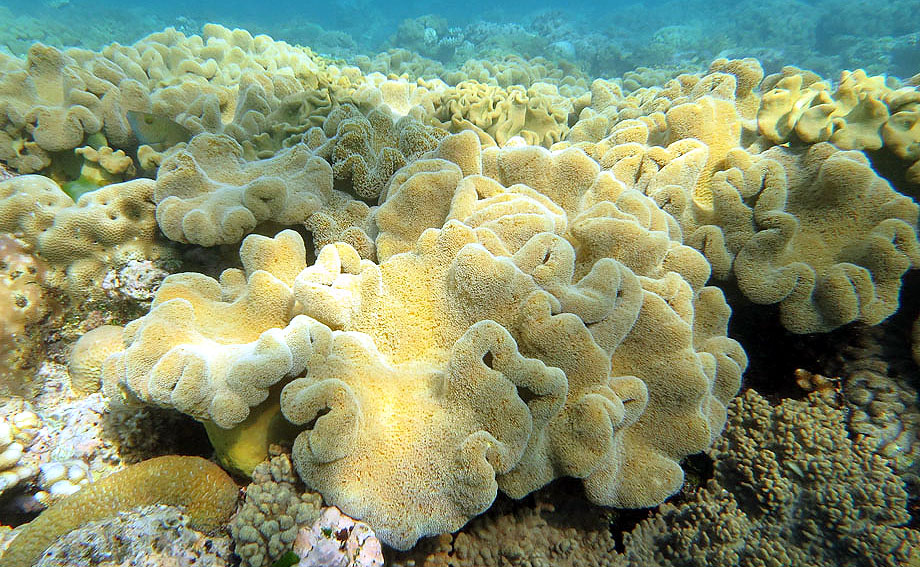

Moving along, it’s important to note that toadstools can get big, too. So big, in fact, that they can literally fill up a large portion of any but the largest home aquariums. Be aware that many can develop a capitulum that’s well over a foot (or two) across, with hundreds of polyps emerging from the top. So, they’ll need plenty of room in an aquarium and usually won’t last long in small tanks before needing more space. It’s difficult to figure out how big a specimen will get though, as it varies depending on environmental conditions and from species to species, with the species identification being difficult to figure out, at best.

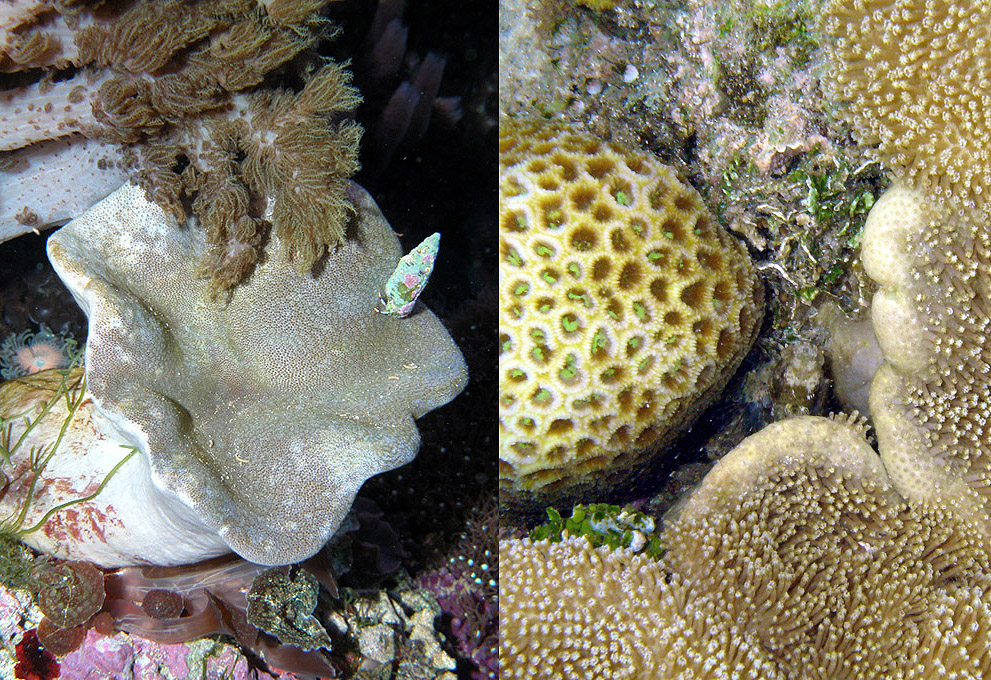

In fact, most all of them are identified only at the genus level (especially in the hobby), because species-level identification usually requires the collection of a few sclerites from a specimen and a good look at them under a microscope, and/or genetic and chemical analyses. Even the pros have difficulty identifying many soft corals, and as noted in Sprung and Delbeek (1997), “Their appearance is highly variable, and the same species from slightly different locations can look radically different.” So, given that sclerite/genetic analysis obviously aren’t an option for us, don’t expect to see too many species names on offered specimens. There are exceptions though, as the yellow variety is quite distinct and is known to be Sarcophyton elegans.

Here’s a look at a few big specimens in Australian and Indonesian waters, all of which are obviously more than a foot across.

Regardless, I mentioned environmental conditions above because water quality and lighting will strongly affect their health growth. Poor water quality is detrimental to the health of all aquarium inhabitants, and all species of Sarcophyton contain symbiotic zooxanthellae like almost all of the other reef-dwelling corals and thus rely on light for survival. Using high-output fluorescent lighting will work fine and will typically result in good growth, but they can be kept under very intense LED or metal halide lighting, as well. Then there are the tankmates…

Don’t think they can’t get so large in an aquarium. This toadstool is taking the whole end of this 150 gallon aquarium, but started as a relatively small specimen.

As hardy as toadstools are, they most certainly can be irritated or even outright burned up by other corals that can come into direct contact with them, or reach them with stinging tentacles. So, it’s best to leave plenty of space between any corals that may harm a toadstool at the time of placement, or in the future as each grows.

A wide variety of corals can also produce and exude a range of toxic chemicals into surrounding waters, producing a flow of nasty compounds that can irritate, stunt the growth of, or even kill other types of corals growing nearby. Things like terpenoids, diterpenoids, and acetates can be released, and all of the corals in any aquarium can be bathed in a low concentration, but potentially never ending flow of these. Soft corals generally lack the powerful tentacles that stony corals posses, but essentially all of them carry a chemical punch, and I suspect that these chemicals are responsible for the lack of growth I’ve witnessed at times.

For example, I have a 125 gallon reef aquarium that is dominated by soft corals, and there’s a lot of diversity at that. I’ve placed four different toadstools in the aquarium, but only one has grown well, while the others have grown little or none. The specimen of Sarcophyton elegans pictured above is one of them.

While it looks perfectly fine, this specimen is a cutting from a much larger one, which was growing very well under similar lighting, but in an aquarium with only a few other soft corals in it. When the cutting was made it quickly increased in size, but after being moved into my aquarium, it just stopped growing. It hasn’t had any problems that I know of, but it hasn’t grown even an inch in over two years. Likewise, two of the other smaller cuttings from other types of toadstools that haven’t grown very much, despite the fact that ALL other types of soft coral in the aquarium have been growing well – including a fourth toadstool cutting from yet another very different-looking specimen. It has grown as expected. So, that’s why I’m under the impression that there’s some form of chemical warfare going on in the aquarium, which shouldn’t be a surprise, really. Water changes and the use of fresh activated carbon and a big skimmer haven’t had any affect that I could see, so I guess I’m just stuck with a few small toadstools and one bigger one.

Toadstools are generally very tough corals, but they can be irritated or injured by some others. Be mindful of this when placing one in an aquarium.

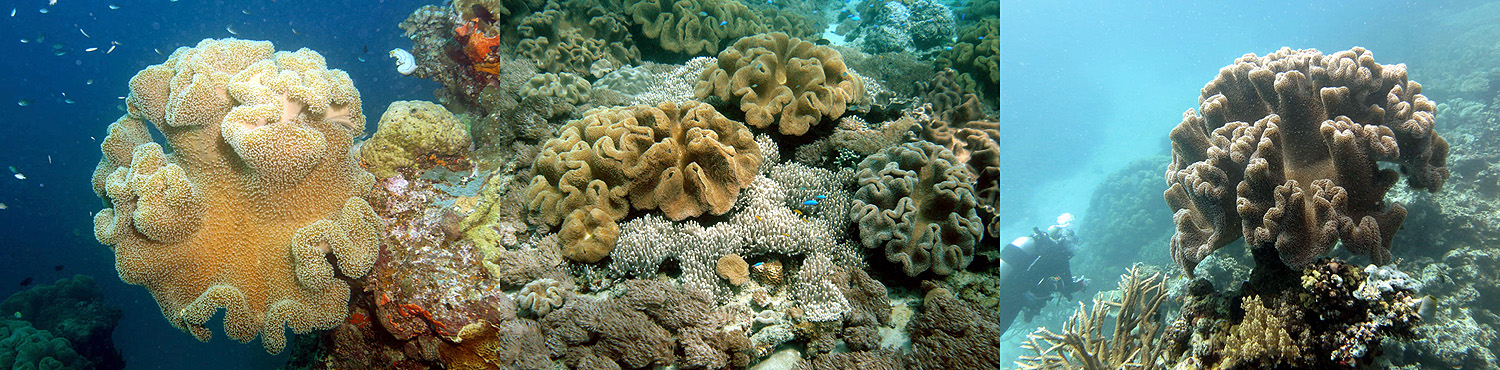

Anyway, like many other corals, toadstools are colonial organisms that can reproduce by releasing parcels of themselves. In particular, they sometimes “auto-fragment” by dropping off bits and pieces of their own capitulum, which can readily grow into whole new colonies. While it’s far less common, they can sprout bud-like projections on their trunks that can drop off and produce new colonies, as well. Even more uncommon, at times a large specimen may very slowly migrate along a surface, leaving small parts of itself attached to the substrate to form a trail of new colonies. Or, these buds may instead slowly migrate away from a stationary parent. Regardless of how they form, it should be obvious that a little piece of a specimen can grow to a full size specimen.

This is a good thing, as toadstools are yet another coral that can be easily propagated by hobbyists. Any of them can be cut up to produce more specimens, and the parent specimen typically heals quickly and without problems. To do so simply cut away a small piece of the top of a toadstool using a razor blade. Or, for a bigger piece you can actually cut off the whole capitulum by slicing through the trunk. The parent specimen should then be placed in an area with a good current to ensure that the cut area stays clean and free of detritus, and the cutting produced should be given something to attach to in a low-current area, or affixed to something manually.

Here you can see one of the ways toadstools reproduce. They can auto-fragment, dropping off pieces of themselves, which typically attach to the substrate near the base of the parent colony and grow from there.

Using cyanoacrylate glue to stick a cutting onto a rock or frag pug often doesn’t work so well. But, I’ve had good luck using some monofilament fishing line and a needle to do the job. All you have to do is run the line right through the bottom of the piece then tie it onto a piece of substrate. The line can then be snipping and carefully pulled out of the specimen later, after it has developed a firm attachment.

You can also purchase and use a perforated breeder box which is usually used to separate baby fish from larger fish in freshwater aquariums. One of these boxes can be hung inside the aquarium with the bottom covered with some pieces of rock, and a cutting can be placed onto them. After anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, cuttings will usually take firm hold of one of the pieces of rock and can then be moved out. Easy.

By the way, when no host anemone is around, don’t be surprised if a clownfish takes up residence in the polyps of a toadstool. A number of other fishes will do this, too.

So, while there can be some issues from time to time, overall toadstools are attractive, hardy, and easy to propagate, making it easy to see why they are a long-time hobby favorite.

References

- Aratake S., et al. 2012. Soft Coral Sarcophyton (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) Species Diversity and Chemotypes. PLoS ONE 7(1).

- Delbeek, J.C. and J. Sprung. 1997. The Reef Aquarium: Volume Two. Ricordea Publishing, Coconut Grove, FL. 546pp.

- Holmes-Farley, R. 2003. Aluminum in the Reef Aquarium. Advanced Aquarist’s Online Magazine, URL: http://www.advancedaquarist.com/issues/july2003/chem.htm

- World Register of Marine Species, undated. URL: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=205483

0 Comments