By Paul Whitby

In the first installment of this series we discussed the eradication of two common pests, aiptasia and majano anemones (which can be read here). While these two pests do not really move around a tank a great deal, they do spread rather fast, which is the main reason people rush to eradicate them. They are also very easy to see and identify in your system. Next, we will turn our attention to a few wee beasties that are not so easily seen, are capable of moving and that are also capable of causing a great deal of damage. This article is dedicated to the coral eating nudibranchs that we may inadvertently introduce into our systems.

Coral Eating Nudibranchs

In the last article I introduced you to a coral eating nudibranch, but one often farmed for the fact that it eats aiptasia. Berghia verucornis, like most nudibranchs will eat only one type of food stuff, in this case aiptasia. Likewise the two aeolid pests nudibranchs commonly seen in the hobby are also named for their feeding habits- the montipora eating nudibranch (MEN) and the zoanthid eating nudibranch (ZEN). Like many pests, these are often brought into the tank on a coral that appears otherwise healthy and over several months the population increases to the point where the damage becomes more and more visible. Both can be readily dealt with, but there are no whole tank treatments at this time, thus prevention is by far a better strategy than eradication.

Identification

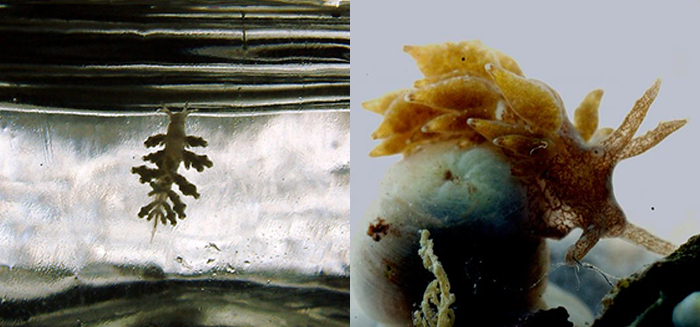

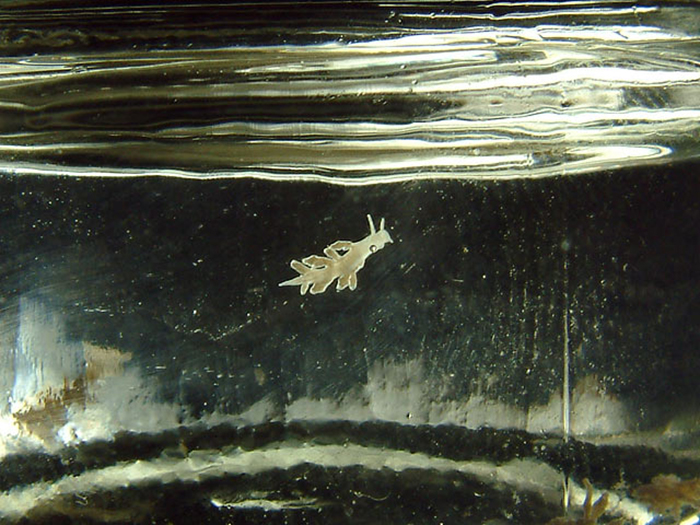

Of the two nudibranchs, the MEN are by far the easier to spot. The Adults are approximately 1/4 inch long and the body and surface exposed gills are bright white with a stringy, almost knotted appearance. By contrast, the ZEN are normally a dull brown color, slightly longer than MEN and with various gill coloration that tends to match the color of the zoanthids they are predating. It is likely that this camouflage is brought about by incorporating the pigments of the consumed zoas into the body of the nudibranch. In the image you can see two ZEN, both with a speckled gill coloration matched to the zoas they have been eating. This makes them extremely difficult to spot as they move around inside mats of zoas. In general, you can spot MENs on the affected coral but ZENs are more often seen on the glass of the tank than on the affected piece. Should you have ZEN in your system, it is likely that you will notice the failure of the zoanthids to open fully and the slow decrease in numbers of each colony. It is still unlikely that you would see the nudibranch itself. MENs are much easier to spot and the damage is quite clear. A slowly expanding region of bright white tissue will begin at the edge of the coral and this will get larger each day as the MENs feed on the living tissue. As the adults get larger it also possible that you will see them on the tissue, especially if you look at night as they are nocturnal. The exact life cycle of these two pests is unknown and controversy remains over whether they can reproduce asexually or not. Irrespective of this, masses of around 100 eggs are laid that hatch in 2-4 days. The young reach maturity 2-4 weeks after hatching. The egg masses of the MEN are small and somewhat tufted, like tiny grains of rice stuck together and always found on the underside of the affected coral, or on an adjacent rock. By contrast, ZEN egg masses are small mucous coated spirals on the sides of zoanthids within the infected mat (an example of a ZEN egg cluster can be seen in the photograph below). Both are tiny and difficult to spot.

Treatment

The best treatment is to not introduce these pests to your tank in the first place. There are several approaches one can take, with QT of each coral the absolute best. However, most people do not have the facilities to isolate each coral separate from all others and thus various commercial dips and treatments have been developed. Unfortunately there are no dips on the market capable of killing the eggs of either species and these kill only the adults. Thus, it is strongly recommended to observe any untoward creatures that are released from the coral during a dip, as opposed to presuming the coral is safe to add to the tank. As an alternative to chemical dips I have often used cold tank water as a simple non-stressful method to remove potential parasites. Should you wish to do this, take some tank water and place it in a jug in the refrigerator for a few hours. The new or infected coral is then dipped and swirled in this water for about 30 seconds or so. During this time, the cold stuns the parasites and the agitation forces them to release from the coral. The coral is then placed back to a holding tank. Once done, I will check the cold water and look for any pests I can see. In general there will be small shrimp, bristle worms and other benign flora, but any nudibranchs (or other pests) will be readily spotted. If no pests are spotted it is likely that the coral is not infected, however if suspect nudibranchs are observed you are now better armed to deal with the potential threat. Should you be unfortunate to spot a nudibranch- of any kind- consider it a pest. The first step to eradication is to kill the adults to prevent further damage. The cold water dip will certainly help, but something a little more toxic such as one of the proprietary treatments on the market is recommended. There are many to choose from and most work well on adults, but any visible egg masses need to be removed by hand. Thus a series of dips spaced over several days to weeks are recommended before one can be confident (but never sure) of eradication. Please note- chemical dips are likely to be stressful to your coral so exercise as much caution as possible when performing repeated dip treatments. Besides proprietary solutions, there are reports from the literature that suggest levamisole treatment kills adults, but can also damage corals. Another option is potassium permanganate treatment which also kills adults but with minimal impact to the coral. This chemical requires care in its handling and an exact dosage needs to be used. With all of these treatments, it is strongly recommended that a great deal of research is done before use.

While prevention is the ideal, it is not often apparent that an issue exists until a coral looks damaged. By then it is unlikely that the coral has encrusted on the rockwork and removal and cleaning of the coral is no longer an option. It is also likely that other corals in the tank may be asymptomatically infested with these predators. In this scenario two options are available. The first requires fragging all of the individual corals you wish to keep, at areas with no visible signs of damage. Where possible, select areas which have no live rock attached. Each frag needs to be treated as if it were a new specimen and dipped prior to moving to a QT system. The main display tank is then stripped of the remaining coral that may be affected by the suspected pest and allowed to go fallow for several weeks to several months. As nudibranchs only feed on one thing, any that remain in the tank will die in this period. The surviving, pest-free frags can be returned. While this process is drastic, it is the approach most likely to succeed.

Another option is to live with the pests and keep the population to a minimum using a combination of biological and mechanical control of the pests. Should you adopt this approach, taking frags of all the affected coral is still advisable should the long-term plan fail. Once the choice pieces are fragged, a program of systematic eradication can be attempted. In the case of the MEN, the approach is made easier by the highly visible parasite. This is not the case with the ZEN. For both, it is important to remove as many adults as possible and keep the population to a minimum. This is best done by observing the tank at night as both pests are nocturnal and zoanthids are more likely to be closed. Arm yourself with a siphon tube, toothpicks, tweezers and a flashlight. Ordinarily a red LED flashlight is the ideal tool for observing nocturnal shenanigans- but in this case a bright light is required to clearly illuminate the scene.

The best time to look is several hours after the lights go out, then light up any affected corals and immediately remove any visible parasites before they return to the shade. In general, the MEN are readily removed by suction, while ZEN may require plucking with a toothpick followed by suction. A neat trick it to attach a toothpick to the end of the siphon hose with an elastic band, which facilitates the removal of any parasites released from the coral. Also, in a tank with ZEN, they will also be found on the glass as well, making removal easier. This needs to be repeated nightly until there are no more adults found. It may be that during this time the corals are irretrievably damaged and death ensues (which is why it is always a good idea to frag each piece once a pest is perceived).

There is however one other trick that seems to work well after the first few days of picking at adults. The technique is based on the initial cold water dip approach for removing pests and is quite simple. During daylight, when the fish population is out and about, and the tank needs a top off of freshwater, take the pipe that you are using to add water and direct the outflow directly into, or over the affected coral. Ideally the freshwater should be cold and the flow strong enough to blow the detritus out from around the coral. The inrush of cold water stuns the hidden adults and sub adults and releases them from the coral tissue. Once released they pass into the water column where it is likely that hungry fish will snack on them. This is also a process that needs to be repeated, but one which can rapidly reduce the numbers of adult pests on a coral. Observing what is blown from the corals will give an indication of the level of infestation. This is an ideal approach for scrolling montipora and zoanthids as the water can easily penetrate the spaces between the plates/polyps. Having several wrasses in the system will certainly help with devouring any nudibranchs released from the coral before they can reattach to the rocks.

Biological Control

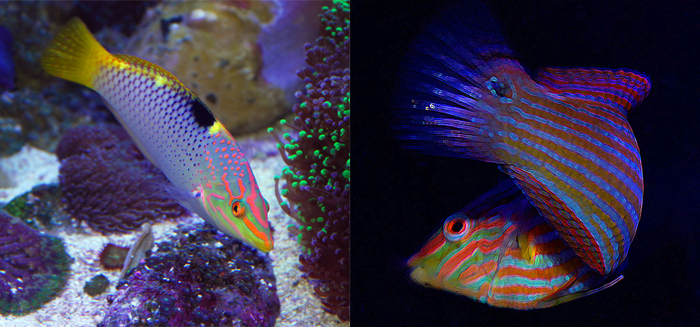

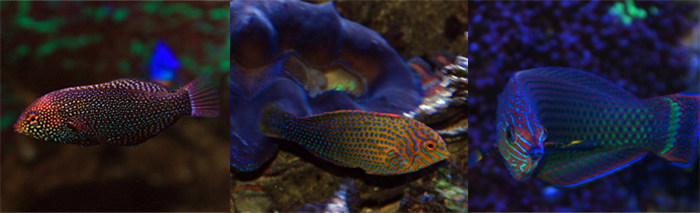

In the above paragraph I eluded to the fact that wrasses will eat free floating nudibranchs, however many wrasses make their living hunting small invertebrates on corals and reefs. This habit can be used to our advantage with the long term control and prevention of infestation of both ZEN, MEN and many other pests. There are an enormous variety of wrasse species available in the aquarium trade, however some are more suitable than others when it comes to pest prevention. To my mind, the best species based on size, cost and beauty of the fish are the smaller Pseudocheilinus species such as the aptly named Sixline wrasse (P. hexataenia). While slightly larger, and certainly more costly, the mystery wrasse (P. ocellatus) is also another great pest predator. Both of these fish are best kept at one per tank due to aggression. As an adult, it is not uncommon for a larger Sixline wrasse to dominate the tank and attack any like colored new additions. Aggression with the Mystery is more limited to other Mystery wrasses. Other wrasses that I strongly recommend include several members of the Halichoeres and Macropharyngodon species. With regards the Halichoeres, my personal favorite is the yellow coris (H. chrysus). This bright yellow wrasse is extremely adept at poking between folds of corals and the deeper recesses of scrolling montipora. Since they only achieve a few inches in size as an adult, Yellow wrasses are an ideal choice for most tank setups. Unlike the Pseudocheilinus species, these can be kept as pairs with the added advantage that more often than not, they will spawn every few weeks. Other Halichoeres species include the beautiful Marble or Checkerboard wrasse (H. hortulanus) and the Melanurus wrasse (H. melanurus), as well as a variety of other species.

In general, juveniles make ideal tank mates but many grow quite large and soon become a pest themselves. While they do not specifically harm things, they are prone to turn over quite large rocks in their incessant hunt for invertebrates. Most, if not all Halichoeres species require a soft sandy bed to sleep in and are not suited to bare bottom systems. The Macropharyngodon are less prone to destructive behavior as adults, but can be somewhat problematic to acclimate to a captive environ due to their preference for live prey as food—exactly what makes them exceptional pest police for your tank as they will constantly hunt for food. This family includes some of the most striking colored fish such as the Leopard wrasse, Potters wrasse, and Dusky wrasse (pictured left to right below). All of these will cohabit with each other and other wrasse species.

The inclusion of wrasses in a new system will certainly help as a prophylactic approach to pest control. The only downside to a heavily wrasse populated tank is that they will hunt and eat any Berghia verucornis (aiptasia eating nudibranchs) that you may add as part of the aiptasia control mentioned in the last article. This is the reason why it is better to farm Berghia in a separate system and add young adults to the infected tank to keep a steady population.

In summary, the coral eating nudibranchs are voracious predators that can rapidly infest and devour corals in a display. A combination of vigilance with new and old acquisitions as well as housing a wrasse or two in a system will certainly help, and hopefully prevent loss of corals to these pests.

0 Comments