Everyone knows that Goniopora are impossible to keep. They always die after a year or so. That’s the word on the street–but it’s not the whole truth. In fact, there have been dozens of reported successes. What has allowed a few aquarists to successfully grow Goniopora?

Over the years, we have “cracked the code” on many kinds of corals and other marine organisms. Many can remember when Acropora were considered impossible to grow in captivity. Today, there are numerous captive-grown strains firmly established in the hobby.

Goniopora is just the latest group of corals with the “keep away” label–but I have no doubt it will soon be put on the “been there, done that” list. I feel we are already on the way to establishing domesticated strains of Goniopora as we have with so many coral and other reef aquarium invertebrates. Captive-grown coral grow faster and are hardier than wild-collected colonies. Not only has the coral itself adapted to captivity but the bacteria, zooaxanthellae, and other symbiotic organisms also have adapted.

That being said, you must do what is necessary to keep these corals alive and thriving. As with Acropora, Goniopora are not the best beginner coral.

An Unplanned Introduction to Goniopora

At Fin and Feather in Groton I would often come across Goniopora in our coral shipments. I put many aside so I wouldn’t have to tell people not to buy them. When the Goniopora were still alive after more than two years in our display tank, I asked myself, Why are they still alive? Why are some growing? Like many coral farmers, I then asked myself, Can I cut them? Over the past year, I have been determined to find the answers to these questions.

Our display system has many things in common with people who have had success in the past. They often had no mechanical filtration, little or no skimming, deep sand beds, and refugiums. The use of some or all of these methods in system design encourage the growth of a variety of small zooplankton and plankton-producing organisms (by spawning, larvae in water column). All of the systems I keep Goniopora in also support Acropora, Montipora, Porites, and other SPS.

Goniopora Is Not Goniopora Is Not Goniopora

Goniopora is a genus of coral. When most people think of Goniopora, they think of Goniopora stokesi. No wonder everyone thinks you can’t keep Goniopora successfully; those things are hard! Goniopora stokesi comes from turbid, nutrient-laden water on a soft substrate. They eat a lot. When I do not feed them five times a week, they shrink.

You can see the light green color, smaller polyps, and shorter tentacles of the frag on the left. Over time, the frag on the left is developing characteristics of the frag on the right.

The range of desired flow, food, and light needs differs among the many species of Goniopora. Some grow quite large, and a mature colony may look like a colony of Porites from a distance. Others have short polyps and are encrusting. Still others are free living on soft substrates.

The genus Goniopora is in the family Poritidae. It seems one can connect the dots between the different species of Goniopora all the way to Porites. Goniopora stutchburyi, with its small polyps and encrusting growth forms, can be mistaken for Porites. In fact, its care is very similar to several forms of Porites we often have success with in aquaria. Identification down to the species level will greatly increase your odds of success.

The growth form and color of Goniopora changes over time in the systems at Fin and Feather. The following picture shows two Goniopora norfolkensis, fragged from the same colony at the same time and placed in separate systems. In this picture, they had been in the same system for two months after over a year of separation. The frag on the right was in the system first.

Another example of change in form and color is the Goniopora planulata I’ve had in my care for over three years. When it first arrived at the store it was bright pink with purple mouths and polyps approximately 5-7mm long. It is now a maroon color with purple mouths and 2.5cm long polyps.

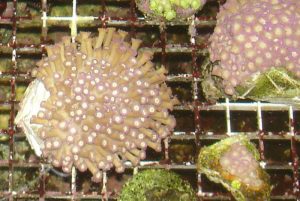

The next series of photos shows a colony of Goniopora palmensis at various intervals after fragging.

Successful Fragging

Dozens of people around the country and the world have been successful with these corals for many years, some as long as nine years and longer. The ability to share with fellow aquarists frags from these long-term colonies will help ensure the establishment of captive strains of Goniopora. Many people have successfully grown daughter colonies dropped by the parent colony.

At Fin and Feather, we have received many G. stokesi with daughter colonies attached. I have yet to see this on any other species, but it is a good possibility that other species have this behavior.

One aquarist said he does a water change with a different salt than he usually uses and his Goniopora will develop these buds. Having control over the asexual methods of reproduction greatly increases the ability of the coral farmer to produce more frags on demand. I have had great success fragging with a Dremel power tool with a diamond wheel attachment.

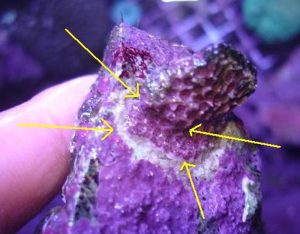

The arrows point to that fast initial growth with two rows of full polyps. On the right side of the colony you can see the area freshly cut.

All frags from healthy colonies have survived at Fin and Feather. The frags and mother colonies often have their polyps extended after a few hours. Growth over fresh wounds is quick, usually showing tissue over bare skeleton within two weeks. I believe this fast initial growth is tissue embedded in the skeleton growing to the surface and developing polyps. I like to mount my frags with tissue as close to the mounting surface as possible. Once the tissue reaches the plug or rock encrusting growth can be as quick as 1 mm a month.

The next step in Goniopora propagation (and for all corals for that matter) is sexual reproduction in captivity. The ability to reliably spawn corals, settle and grow them will have many benefits, including larger numbers of offspring and genetic diversity. Methods are now being developed and I expect that soon you will be reading about how to spawn your coral.

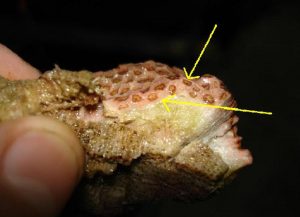

After one month, the area on the right is completely healed with new polyps. In the middle of the picture you can see tissue and skeleton growing out and away from the old skeleton.

Identifying Goniopora Species

When I receive a list of available Goniopora from a wholesaler, I see, “Red Goniopora, Blue Jewel Goniopora, Green Flowerpot.” Wow, thanks for the clarification. I must be fair though; for wholesalers to correctly identify most Goniopora to species level would be time consuming and not conducive to a higher profit margin. A few species may be identified by external characteristics rather accurately, but most need a detailed inspection of the corallites with magnification.

Corallites are the skeletal features associated with each polyp in the coral colony. For my identification, I cut sections of the coral and bleach them to expose the skeleton. Some imported colonies already have areas that have died back and skeleton is exposed. If these corallites are not eroded or grown over with organisms, you may be able to use them for identification. This may be a little less painful than the idea of cutting healthy tissue, then bleaching it.

I then use the coral identification key in JEN Veron’s Corals of the World and the associated CD-ROM. Taking into account growth form, polyp morphology, and corallite details, I am able to determine the species of the Goniopora I am working with. On several specimens, I have had to get a second opinion due to variability within species.

Thankfully, compared to other coral genuses, one can rather accurately come up with a species identification with Goniopora. Some other corals are hard to even pin down to genus.

Knowing which species you have in your care allows you to provide a care and feeding regimen that will be more suited to that specimen and that will increase your chances for success.

One interesting example of this is found in two types of Goniopora polyformis at Fin and Feather. The first one we received and have had for more than two-and-a-half years. It is encrusting with short brown polyps. More recently, we’ve received several bright green Goniopora with long polyps and a massive growth form with an encrusting base. By casual observation, it is easy to see how these two corals might be mistaken for two different species. These differences could be due to geographical or environmental reasons. Coral species often display different characteristics at different points along their range. Many species also show changes in growth form in different environments.

Feeding your Goniopora

In just the past two years we have seen the introduction into the hobby of several very exciting new small-particle-sized foods with good nutrient profiles. These include Cyclop-eeze, Hikari Frozen Rotifers, and DT’s Oyster Eggs. The design of plankton-friendly systems, proper coral husbandry in terms of water conditions, and the direct feeding of these quality foods will help insure long term success.

Even if you cannot positively identify the species of Goniopora in your care, you can figure out what it may eat. When trying foods, it is important to note the difference between a stress reaction and a feeding reaction. If you target-feed with a syringe and are too forceful with the flow, the coral will quickly retract its polyps in defense. A polyp retraction in response to stress is quick and fluid, and often spreads across the whole colony. However, polyp retraction for feeding is slower and jerky. Some polyps will bend toward the food, retracting one side of the polyp in rhythmic pulses. The polyp will then sit there with its mouth on the food and eventually fully retract. There is often active pronounced tentacle curling as they capture food particles. Goniopora burgosi has the most active tentacle curling of all the Goniopora at Fin and Feather.

I did not directly feed my Goniopora for over two years–but as soon as I began direct feedings, I noticed an increase in the speed of growth. I now feed all my Goniopora generously with a variety of the foods they have shown feeding reactions too.

At Fin and Feather, I have used a variety of foods for my Goniopora. I have determined what kinds of food some Goniopora have shown a definite feeding reaction to. This list of foods is growing and is not exclusive. There are many foods out there waiting to be tried, and many more to be developed.

Many people have supplemented by feeding with phytoplankton. In my studies of Goniopora, only one variety showed a feeding reaction to phytoplankton alone. However, many kinds of zooplankton eat phytoplankton, which are in turn eaten by the Goniopora.

In the profile list that follows you will see food mix and light food mix. A goopy food mix I use for larger-polyped Goniopora is 1 part crushed brine shrimp cube to 2 parts crushed Cyclop-eeze flake,1-2 parts frozen rotifers, and 5-6 parts phytoplankton/ Cyclop-eeze juice/ DT’s oyster eggs. Light food mix has twice as much liquid food for a lighter consistency, a better food for smaller-polyped species, but also accepted by larger-polyped species.

When feeding your Goniopora, you will quickly find many other aquarium inhabitants find the food mighty tasty too. You may have to beat back an onslaught of fish and invertebrate food raids. Nassarius snails will be there in seconds. Fish and serpent stars may gleefully steal your Goniopora’s food. Shrimp will take the food and some of your Goniopora too, ripping right through the tissue, causing much damage at times. Some people have built feeding traps-high-tech devices such as one- and two-liter bottles placed over the coral so it may be fed in peace.

In my opinion, smaller-sized food particles are better than larger ones. I will be conducting a thorough food study to determine which foods are more conducive to growth. Until then, I can only tell you what I have observed. During the six-week period when I fed DT’s Oyster eggs exclusively to all my Goniopora in three different systems, I noticed faster encrusting growth and longer polyp extension.

Until we get some definitive data, I would suggest using foods with a good nutrient profile and smaller particle size. The systems that people have successfully kept Goniopora in can produce much plankton, eggs, and larvae. These prey items can be quite small. A Goniopora stokesi can ingest a full grown brine shrimp, but is that the best for them?

Several new foods are in pre-market production and may prove to be very beneficial to the aquaculture of Goniopora, and other still difficult- or impossible-to-maintain corals and invertebrates. I have had many opportunities to try some unusual potential foods. I had newly imported urchins spawn, so I grabbed a syringe, sucked up the eggs, and fed away. All the Goniopora I fed them to showed feeding reactions, some stronger than others. Peppermint shrimp eggs were taken by many kinds of Goniopora, as was Striped Bass Blood. Cleaner shrimp eggs and emerald crab eggs were only ingested by some. Dead cleaner shrimp eggs were not ingested at all.

This difference in feeding reactions shows some potential new foods are more suited for growing Goniopora. I believe invertebrate eggs and larvae would be excellent foods for development in the hobby. Many have great nutrient profiles, and some, such as urchin eggs, are ingested by many corals.

I believe the availability of proper food is the main factor in many Goniopora successes. Whether it’s the higher amount of dissolved organics, higher plankton levels in systems with refugiums, and little or no skimming or direct feeding, with forethought in system design and husbandry techniques we can be successful with many species of Goniopora.

Goniopora Species Requirements

I have created a small profile of each species under my care, each with a table of methods of husbandry that has worked successfully. This chart may prove useful for providing proper care for your Goniopora. You may find your specimen may have different requirements than those listed here, due to natural variability.

Goniopora stutchburyi Light: Moderate to High Flow: Moderate to High Food: DT’s Oyster Eggs, Cyclop-eeze juice (left over liquid from thawing frozen Cyclop eeze), Liquid Life Plankton (may be too large), light food mix Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Goniopora burgosi Light: Moderate to High Flow: Low to Moderate Food: Hikari Frozen rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, DT’s Oyster eggs, Cyclop-eeze juice, Light Food mix Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood, Emerald Crab Eggs, Cleaner Shrimp Eggs

Goniopora palmensis Light: Moderate to High Flow: Moderate to High Food: no noted feeding reactions. Continues to grow well. Perhaps just absorbs dissolved organics and ingests minute plankton and bacteria from the system Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Goniopora somaliensis Light: Moderate to High Flow: Low to High Food: DT’s Oyster eggs, Cyclop-eeze juice

Goniopora norfolkensis Light: Low to High Flow: Low to Moderate Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Goniopora planulata Light: Low to High Flow: Low to Moderate Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Goniopora polyformis Light: Low to High Flow: Low to Moderate Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Goniopora djiboutiensis Light: Low to High Flow: Moderate to High Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs, crushed brine shrimp cubes

Goniopora eclipsensis Light: Med to High Flow: Moderate Food: DT’s Oyster eggs, Cyclop-eeze, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, food mix

Goniopora pandoraensis Light: Med to High Flow: Low to High Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs

Goniopora tenuidens Light: Moderate to High Flow: Low Food: DT’s Oyster eggs, Cyclop-eeze, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, food mix

Goniopora stokesi Light: Moderate to High Flow: Low Food: Hikari Frozen Rotifers, Liquid Life Plankton w/ Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze, Cyclop-eeze juice, Food mixtures, DT’s Oyster eggs Experimental foods: Peppermint Shrimp eggs, Urchin Eggs, Striped Bass Blood

Conclusion

Goniopora are no longer impossible. With knowledge of the species you are working with, proper system design, and appropriate foods, your chances of success are greatly increased. Goniopora are for the aquarist dedicated to providing the proper care for these challenging yet possible to keep coral. As our knowledge of this genus grows we all can play a part in sharing the methods of our success. Careful observation and accurate notes will do much to help the hobby advance its goal of successfully keeping these and the many other beautiful ocean creatures in our aquariums.

References

- Borneman, E. H. 2001. Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry, and Natural History. Microcosm/TFH, Neptune City. 464pp.

- Borneman, E.H. 1997. A Death In the Family? The Mystery of Goniopora, Aquarium Net magazine. http://www.reefs.org/library/aquarium_net/1197/1197_3.htm

- Toonen, Rob. 1999. Goniopora success?! Reefkeepers email list, December 1999.

- Toonen, Rob (2001) Goniopora: Why do success rates with this coral remain so low? Freshwater and Marine Aquarium (FAMA) Magazine, Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 142-158.

- Sprung, Julian. 2002. Captive husbandry of Goniopora spp. with remarks about the similar genus Alveopora, Advanced Aquarist’s Online Magazine, December 2002.

- Veron, J.E.N. 2000. Corals of the World. Australian Institute for Marine Science, Townsville. 3 Volumes.

0 Comments