Springtime in New York brings the return of migratory birds and fishes, hibernating reptiles and amphibians, and if you know where to look, massive swarms of the mysid shrimp, Neomysis americana. These mysids provide great opportunities for hungry marine life and thrifty aquarists.

After a long cold winter it’s not easy to stay positive about life in a temperate climate like New York. But what we lack in fair weather and coral reefs, we make up for in seasonal abundance. As days lengthen, providing more sunlight to our surface waters, massive plankton blooms occur along the coast. They are fueled by a combination of sunlight and nutrients which are made available by the winter breakdown of the thermocline, allowing deep nutrient-rich water to come to the surface. It usually begins in February with a diatom bloom that lasts a few weeks and colors our bays a greenish-brown. As the diatoms are nearing peak density, copepod populations begin to increase, and for a period of about two weeks around the end of February and beginning of March, they dominate the plankton community and can be found in staggering abundance. A combination of ecological factors ensures that these heydays are short-lived. Diatoms deplete nutrients necessary for productivity, then copepods deplete diatoms; but just as the copepod bloom occurred in response to the presence of diatoms, other organisms time their lifecycles and migrations to take advantage of the copepods. Near the end of the copepod bloom, we start to see massive numbers of moon jelly ephyrae and medusae from hydrozoans. This is when the mysids usually appear. Although at least six species belonging to the family Mysidae (including one invasive from Europe) can be found in NY, the most abundant, by far is Neomysis americana. This is the species that swarms in shallow bays and estuaries all along the northeastern US in early spring. Numerous migratory species, particularly members of the herring family, time their return to take advantage of these swarms. Not surprisingly, their predators: osprey, cormorants, bluefish, and striped bass follow close behind.

As an aquaculturist, I am a pretty big consumer of frozen mysids, so it’s hard to resist taking advantage of these blooms. It’s a great excuse to spend some time outside, on the water, and it saves me a few dollars. It’s also comforting to know exactly where they are from and to have complete control over their handling. When I open a package of commercial mysids and am unimpressed with the look or smell of them, I often wonder about the standards for food handling when it’s not for human consumption. I think: “How many times might this package have thawed along the supply chain?” Bagging my own mysids removes any of those doubts.

I am often asked why I don’t catch more of them and sell them, or why I don’t just catch all of my own mysids. Here are a few reasons: Catching and selling any kind of marine life from the wild would make me a commercial fisherman and require a commercial fishing license. I have no intention of going down that road. I already have a job that I like very much. Also, these blooms aren’t exactly reliable. I have no way of knowing exactly when they will show up or how long they will last. Some years the swarms last for up to two months. Other years they only last for a few days. If you’re having a busy week, you can miss the whole thing. Another limiting factor is that access to shorelines suitable for collecting mysids is limited, and if you do find a good spot, it can easily be shrimped out within a few minutes. More mysids will usually swarm in to replace the ones you caught or scared off, but you’ll need to wait.

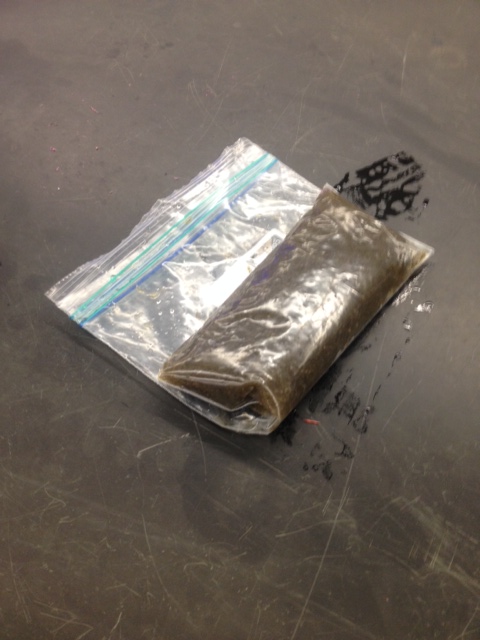

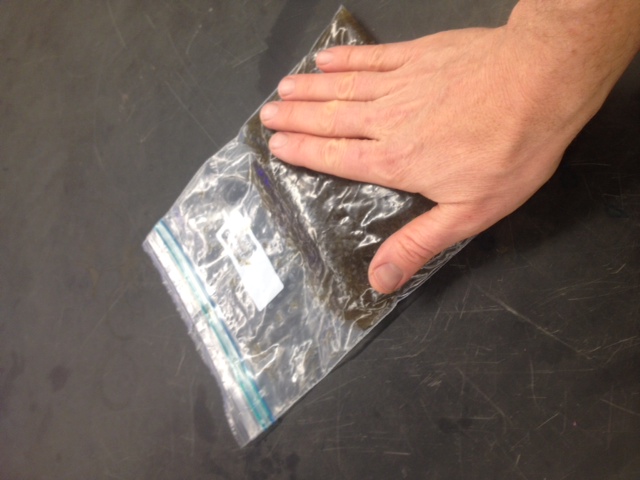

If you are interested in getting out catching some mysids yourself, here’s some advice. Look for calm, protected bays with some fresh water input. Right now I’m finding the best swarms near the mouths of rivers and creeks in salinities between 10 and 20ppt. They often swarm right next to bulkheads and docks, which makes catching them with a long-handled dip net very easy. You need a mesh size of no more than about 5mm to keep them in the net. If you are planning to freeze them, I suggest bringing a cooler of ice and bagging them in the field. Resist the temptation to keep them in high densities in a bucket of water. They will begin dying within minutes as they deplete the oxygen. If you want really high quality frozen food, it’s best to freeze them while they are still alive. I use a small aquarium net to transfer the mysids from a bucket, into quart freezer bags. I get all the shrimp to the bottom of the bag, and then I roll it from the bottom to remove all of the air. This is very important in preventing freezer burn. The next step is to press the contents gently on a flat surface, spreading them evenly. It’s important to not over-fill the bags. Think of the shape of the mysid flats you get from Piscine Energetics or Hikari. They are well suited to breaking off small manageable portions. If you overfill the bags, you will end up with thick blocks of shrimp that will be extremely difficult to break.

We can probably count on at least a couple of more weeks of abundant N. americana around here, and as long as they’re around, I’ll continue to fill a few bags each day. It will save me some money and allow me to diversify the diet of the fishes in my lab, but naturally I also plan to continue using the same high quality mysids I’ve been getting from Hikari and Piscine Energetics for the last 15 years.

Great Post. I went to the Peconic River today and thay were still there! I got 3 bags full. Thanks for the tip, Todd.

Oh, I forgot to say, I am feeding them to my 4 Lined seahorses and they love them!

is this behind atlantis? what collection pt is this? gps location? thanks.

Its the dock directly behind Atlantis off the parking lot along the river. I got 5 ziplock bags full about 3 weeks ago. Don’t know if they are still there!

thanks for the info.