Owing to its extensive natural range, S. cristata is appropriate for countless types of biotope aquaria. Photo by Stefano Guerrieri.

One could scarcely refer to the Molly Miller blenny as an “ornamental fish.” To be sure, it is one of the most hideous animals that an aquarist’s money can buy. With its bulbous, bony head, huge eyes and a crown of bristlelike appendages, it bears the visage of something out of a Dr. Seusian nightmare. In lieu of the bright hues and gaudy patterns characteristic of so many other coral reef fishes, it is colored only with blotchy patches of drab browns, greens and grays. Lacking a well-developed swim bladder, it more or less lays on the bottom, clumsily scooting about in a most ungraceful manner. Really, as far as outward appearances go, its only saving grace is the sad consolation of being (at least to some fishkeepers) so ugly that it is cute.

That, of course, is not much of a consolation. Actually, this species would have negligible value in the aquarium fish trade (apart from the few peculiar fishkeepers that always seem to love the ugliest creatures) if it were not for a couple very important attributes.

S. cristata is distinguishable by its prominent nuchal cirri; as it matures, the cirri appear–often one by one–to eventually form a tufted patch atop the head. Photo by Chris Turnier.

While it may not be the best looking fish out there, the Molly Miller blenny does possess an abundance of something aquarists universally refer to as “personality.” The antics of this intelligent, excitable and oftentimes scrappy animal are well known–indeed celebrated–among those who have kept them.

All of that being said, the Molly Miller blenny might best be described as a “utility fish.” This not-so-fussy eater has earned a reputation as an effective aquarium scavenger; it is known to feed on nuisance algae and detritus, and is widely reputed to feed on cyanobacteria and Aiptasia spp. sea anemones. If even half of these reports hold up to truth, the Molly Miller blenny could truly be the preeminent clean-up critter of the marine aquarium fish trade. To note, it may be the first fish species to be commercially tank bred for this purpose.

Salarias spp. are suspected by some to be (at least in certain locales) frequently exposed to cyanide by unscrupulous collectors; a tank bred alternative to this valuable algae-eater could be well received by many hobbyists. Photo by Kenneth Wingerter.

The Molly Miller blenny is not particularly difficult to maintain in captivity; actually, there are few marine fish species that are as amendable to aquarium conditions. This can be attributed largely to its various adaptations for subsistence in harsh, unstable environments.

Natural history of the Molly Miller blenny

Range and habitat

The Molly Miller blenny (Scartella cristata Linnaeus, 1758) has an extraordinarily wide distribution. It occurs in rocky or coral reefs of the Northwest Pacific Ocean (Japan and Taiwan), the Western Atlantic Ocean (from Florida to Brazil), the Eastern Atlantic Ocean (from Mauritania and the Canary Islands to South Africa), and the Mediterranean Ocean (from Spain to Greece). While it is found in temperate, subtropical and tropical environments, it appears to fare best in warmer climes; indeed, global warming has been implicated as the cause of its growing presence in Southern Europe.

S. cristata usually inhabits very shallow waters, from tide pools down to ~10 m (i.e., the upper photic zone). However, maximal population densities (comprised mainly of small and intermediate size classes) occur at ~2-4 m depth. In general, its abundance sharply decreases with increasing depth.

Subsequent to post-larval settlement, S. cristata is non-migratory. It is primarily benthic. It favors areas that feature hiding places in the form of stone crevices, bioconcretions (abandoned snail shells, barnacle tests, etc.) or fronds of algae. Its dull coloration and dappled pattern serve as camouflage in these environments. Observations of grow-out stock at Sustainable Aquatics suggest that it can change coloration to match different substrata.

Sexual dimorphism is rather pronounced in S. cristata, though only in late maturity (here shown is a male to the left and a female to the right). Photo by Chris Turnier.

Where suitable substrate cover is ample, it typically reaches population densities of 0.4 to 0.9 individuals/m2. Still, it has been observed in prime habitat at densities as astonishingly high as 9.6 individuals/m2, accounting for more biomass than that of all other resident fish species combined.

Diet and feeding behavior

S. cristata exerts an enormous influence on the trophodynamics of the habitats in which it occurs. It feeds heavily on epilithic (especially filamentous) algae; nevertheless, it is best regarded as an omnivore, rather than an herbivore, for the reason that in the course of grazing it ingests a very wide variety of items included in the epilithic algal matrix (e.g., detritus and microorganisms). Further, it may target certain small sessile invertebrates (e.g., Aiptasia spp. anemones). It has even been observed feeding on fish carrion. In one gut content analysis, 41 different food items could be identified.

S. cristata feeds mainly during the day. Its feeding activity increases steadily throughout the morning hours, leveling off in the early afternoon, and then sharply decreasing until cessation at dusk. Bite frequency rises and falls with temperature. Season and location have been found to influence its diet and feeding patterns, indicating a high level of trophic versatility. The diet of subjects examined in one study varied, depending upon site and time of year, from 25-55% algae and from 35-62% detritus.

Development and reproduction

The basic adult morphology of S. cristata is quite characteristic of the Blenniidae. It has a compressed, elongated body. It lacks scales. It has large, well-developed pectoral fins, a long, continuous dorsal fin and reduced pelvic fins. It is a smallish fish, reaching a maximum length of approximately 12 cm (though they typically reach only 10 cm).

Individual males can tend nests comprised of eggs from several females; the multiplicity of this brood is evident by the bands of contrasting colors (youngest eggs are pink). Photo by Chris Turnier.

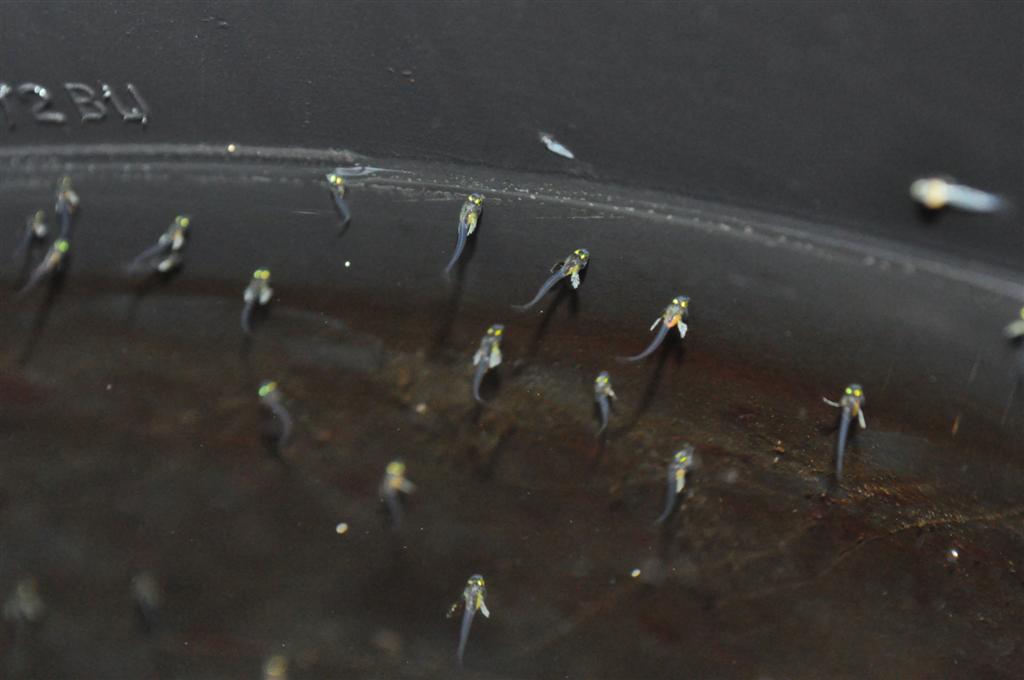

Larvae are relatively large, hatching at about 3 mm and undergoing metamorphosis at 10-11 mm. Settlement occurs around 30 days post hatch at 11-18 mm. Prior to settlement, the head and pectoral fins are heavily pigmented, while trunk pigmentation does not extend laterally far beyond the mid-body. Highly reflective blue-green pigments highlight the eyes dorsally. Consequently, when viewed from above against a dark bottom, larvae have the curious appearance of tiny flies. Little original pectoral fin pigmentation is evident in recently settled individuals. Though its size gap at settlement is rather narrow (~1.5 mm difference), significant discrepancies of size among juveniles is common even among individuals from the same brood.

Sexual dimorphism is evident shortly after settlement. While the first anal spine is clearly visible in males, it is inconspicuous in females. At >15mm, the urogenital opening forms a papilla in males but is covered by a fleshy hood in females. However, sexual dimorphism is much more evident with further maturity. Males typically become darker, larger and more slender, have a fuller, more continuous dorsal fin, and develop a more conspicuous nuchal crest. Breeding males have fleshy lateral extensions at the tips of the anal fin rays and bear spatulate pads on the first-two anal spines.

Inconsistent growth rates are already apparent amongst this two month old group of siblings. Photo by Kenneth Wingerter.

Functional sexual maturity may be reached in as little as 18 weeks. Some individuals (particularly breeding males) may establish territories and defend them with great determination. Upon securing an acceptable nest site, breeding males engage in conspicuous swimming movements to attract the attention of females. An interested female follows the male into the shelter for a brief inspection of the nest site. If satisfied, she will back in and begin depositing eggs on the shelter walls. If there is enough space within the shelter, the male will immediately fertilize the eggs as they are laid.

Each clutch consists of around a few hundred eggs; however, males are capable of tending nests that include multiple clutches from different females, and so may brood a thousand or more eggs at a time. Data gathered from a survey of one Floridian population suggest that an average of 5.5 females contribute to each nest.

Individual nests often contain clutches that have been fertilized by multiple males. Surreptitious fertilizations of “bourgeois” male nests by “sneaker” males are rather common among Molly Miller blennies; indeed, this species exhibits some of the highest frequencies of cuckoldry of all nest-tending fishes. Data from the above-mentioned survey indicate that over 12% of progeny may be sired in this manner.

Eggs hatch in the evening, usually on Day 8 at 78°F. There is no parental guardianship of the larvae. Newly hatched larvae are carried by outgoing currents to open water, where they almost immediately begin feeding on small zooplankton.

S. cristata occurs in a wide variety of color morphs; pigmentation may be affected by age, sex, location, physical environment and perhaps even diet. Photo by Chris Turnier.

Selective breeding of varieties such as this red morph may produce captive stock that is decidedly more attractive (at least to some aquarists) than typically encountered wild-type strains. Photo by Kenneth Wingerter.

Aquarium husbandry

Aiptasia and cyanobacteria are common sources of frustration for marine aquarists. Photo by Chris Turnier.

As it is adapted to the ever-fluctuating conditions of the intertidal zone, the Molly Miller blenny makes for an exceptionally resilient aquarium fish. Even the passably informed novice hobbyist should have little trouble successfully maintaining this animal in captivity. It can be properly housed in most types/sizes of tank. Particularly if multiple specimens are housed together, ample living space will of course be appreciated. However, maximal stocking density will be determined mainly by number of available hiding places, rather than tank size.

To say the least, feeding Molly Miller blennies is uncomplicated. While there are few, if any, reports of Molly Miller blennies targeting desirable aquarium animals, it is worth noting that they can potentially disturb certain creatures (e.g., tridacnid clams) by their intensive grazing. They will accept virtually any kind of aquarium food that they are presented with.

More notably, they have a taste for items commonly encountered by aquarists as various pests and plagues. Their propensity for herbivory and detritivory is above dispute. Interestingly, it may be possible to use them to control Aiptasia.

A simple experiment performed at Sustainable Aquatics has demonstrated the Molly Miller blenny’s appetite for Aiptasia. Two cubicles in a large, recirculating system were emptied of fish. Each cubicle contained a similarly sized population of Aiptasia and red microalgae (unidentified benthic rhodophyte), as well as an equivalent amount of detritus. A tank bred, four-month-old S. cristata specimen was placed into one of the two cubicles. The fish did not receive supplemental feedings throughout the trial. By Day 2, there was a marked decrease in Aiptasia and algae populations as well as a reduction in the amount of detritus in the cubicle containing the fish; no changes were observed in the adjacent cubicle. By Day 10, much of the algae, most of the detritus and all of the Aiptasia had been eliminated. The fish was transferred to the adjacent cubicle after 10 days. Over the next 10 days, a very similar pattern was observed in the cubicle containing the fish; during this same time, no Aiptasia, some algae, and significant amounts of detritus reemerged in the vacated cubicle. While the results of this experiment do not conclusively prove any of the aforementioned claims circulating within the hobby, they do suggest that the presence of S. cristata can suppress proliferation of microalgae and Aiptasia, as well as reduce detritus accumulation.

Captive breeding of the Molly Miller blenny is possible, though not easy. While it spawns readily, its larvae are fickle and demand a rather high level of care; even well practiced fish breeder Dr. Matthew Wittenrich has described its larviculture as challenging. One major impediment to the commercial scale production of this species is the relatively large amount space required for grow-out; this aggressively territorial fish will begin to suffer from crowding at only a couple months of age in the typically bare, unsheltered culture environment. And, ironically, they can eat a production facility out of business.

Still, the culture of Molly Miller blennies for the trade is a worthwhile endeavor, for it presents a more sustainable alternative to any wild-caught herbivore, detritivore or Aiptasia-eater.

In this feeding trial, S. cristata (visible in the back of the right cubicle) clearly reduced detritus, algae and Aiptasia. Photo by Chris Turnier.

Conclusion

By most standards, the Molly Miller blenny is a spectacularly ugly little fish. Whatever it lacks in physical attractiveness, however, is more than remunerated with character. In addition to being fairly interesting to observe and remarkably hardy, it has proven itself to be useful for cleanup and control of various nuisance organisms. Hence, while it might not be a particularly “ornamental” fish, its mere presence can–by virtue of its unusual feeding habits–help contribute significantly to the beauty of display aquaria. The recent availability of tank bred specimens will almost certainly increase its appeal among those aquarists that favor cultured livestock.

Kenneth Wingerter

Process Biologist

Sustainable Aquatics

110 West Old Andrew Johnson Hwy

Jefferson City, TN 37760

[email protected]

This individual reportedly changed its color, apparently to blend in with a dark substrate. Photo by Amy Cole.

References

- Nieder, Jurgen, Gabriele La Mesa and Marino Vacchi. 2000. Blenniidae along the Italian coasts of the Ligurian and the Tyrrhenian Sea: community structure and new records of Scartella cristata for Northern Italy. Cybium 24(4): 359-369.

- Ditty, J. G., R. F. Shaw and L. A. Fuiman. 2005. Larval development of five blenny (Teleostei: Blenniidae) from the western central North Atlantic, with a synopsis of blennioid family characters. Journal of Fish Biology 66: 1261-1284.

- Almada, Vitor C. and Ricardo Serrao Santos. 1995. Parental care in the rocky intertidal: a case study of adaptation and exaptation in Mediterranean and Atlantic blennies. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 5: 23-37.

- Berry, P. F., R. P. van der Elst, P. Hanekom, C. S. W. Joubert and M. J. Smale. 1982. Density and biomass of the ichthyofauna of a Natal littoral reef. Marine Ecology Progress Series 10: 49-55.

- Topolski, Marek F. 2001. Vertical distribution, size structure, and habitat association of four Blennidae species on gas platforms in the northcentral Gulf of Mexico. Master’s thesis. Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama.

- Mendez, T. C., R. C. Villac and C. E. L. Ferreira. 2009. Diet and trophic plasticity of an herbivorous blenny Scartella cristata of subtropical rocky shores. Journal of Fish Biology 75: 1816-1830.

- Nieder, J. 1997. Seasonal variation in feeding patterns and food niche overlap in the Mediterranean blennies Scartella cristata, Parablennius pilicornis and Lipophrys trigloides (Pisces: Blenniidae). Marine Ecology 18(3): 227-237.

- Mackiewicz, Mark, Brady A. Porter, Elizabeth E. Dakin and John C. Avise. 2005. Cuckoldry rates in the Molly Miller (Scartella cristata; Blenniidae), a hole-nesting marine fish with alternative reproductive tactics. Marine Biology 148: 213-221.

- Thresher, Dr. R. E. 1984. Reproduction in Reef Fishes. T.F.H. Publications, Inc.

- http://www.reefcentral.com/forums/showthread.php?s=f2367f34d6d3da3b011e67c64232d976&postid=7644128

0 Comments